By: openDemocracy

Source: openDemocracy

What semblance of a debate on whether Egypt’s policies combating terrorism may be effective died on 24 November 2017 when Egypt witnessed one of its deadliest ever terrorist attacks.

Over 300 people were killed and several hundreds injured by a gang of militants inside the Rawda mosque in Bir-Al-Abed in northern Sinai.

A month prior, 54 security forces members were ambushed 135 km south west of Cairo, a clear sign of a failing counter insurgency policy.

Based on the quality of policies in place, numerous analysts had predicted the deterioration in the security situation in Egypt early on. Few attempted to give Egypt the benefit of the doubt, writing off earlier failures as poor execution. The debate is now over.

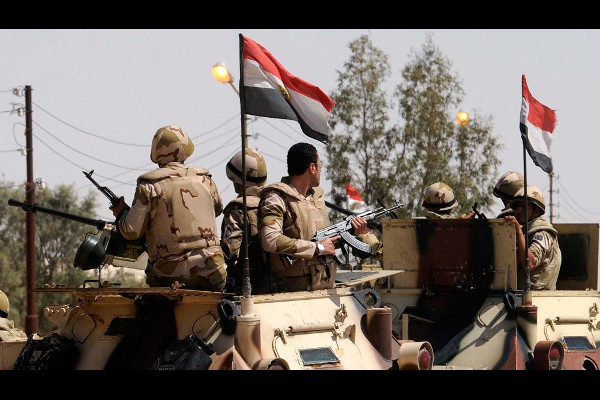

There is no doubt that Egypt’s policies have failed. Sisi’s vow to use ‘brute force’ to end extremist activity in Sinai indicates that no amount of policy advice will sway current leadership from its trajectory.

Yet even as the outlook is bleak, a few other questions currently surround the latest terror incident and have not been as conclusively resolved.

Repression vs ideology

One of the more enduring questions in Egypt (and indeed other Middle Eastern countries) centers around whether extremism is a result of repressive measures undertaken routinely by the state or whether the violence is inherently and unavoidably present within the fabric of the ideology of Islam.

Following the Rawda Mosque attack and many previous others, some placed all the blame purely on ideology, claiming that these violent actions come from violent ideas that are derived from violent verses.

The claim is that violence is a consequence of ideology and Islam in particular, irrespective of repression. Others claimed it is repression that radicalizes people and causes the extreme violent reaction.

While the debate focuses on whether to blame the state or Islamist ideology, simplifying either side would not be accurate.

Blaming repression for the rise of extremism can be countered by the quality of the violence that is produced. Many around the world have been repressed but have not reacted with indiscriminate violence and rhetoric that accompanies extremists who associate themselves with Islam.

The violence is too righteous and extreme to simply be a reaction to repression. To blame Islamist ideology alone does not fully explain it because the majority of Muslims are peaceful and numerous Muslim countries have not devolved into producing such extremist groups.

The reality is that ideology never develops in a vacuum. It largely depends on the context surrounding it.

In order to grow in numbers whatever movement that subscribes to an ideology must be fed with new supporters. Repression is the simplest way to radicalize.

In Egypt, the extreme conservative Wahabi ideology is rampant enough to absorb new recruits looking to live out their radicalization.

To simplify, Egypt’s problem isn’t just repression or violent ideology, it’s sectarianism, intolerance, violence, uncritical support of authority, injustice and brutality.

While the extremists can be blamed for their violent actions and the murder of innocents, we cannot blame them for being provided the perfect breeding ground for new recruits.

That can almost certainly all be blamed on the state along with a culture of violence and the shutting down of real debate as a modus-operandi.

State responsibility

Another question that arises as a direct result of the Rawda massacre is whether the state is responsible for this incident in particular.

After all, how can the state protect people praying in a mosque on a Friday with so many mosques all over the country and limited security personnel in comparison.

This is an argument also made earlier when a bus full of Coptic Christians heading towards a monastery was stopped and many of its passengers executed in May 2017.

With all the roads in Egypt, how is it possible to protect all of them? Besides, we cannot always blame the state for everything. Many have made that claim including a leading human rights figure.

This argument raises the question, when do we accept the failed policies of a state and start holding the state accountable? Can we really isolate the incident of the mosque shooting from the general context in northern Sinai for which the state is responsible?

Add to the mix the fact that ISIS has issued threats to the inhabitants of the town of Rawda for practicing Sufism, and no additional protection was provided to the town.

How can one then not blame the State?

What appears to be a long standing policy of not investing in the development of north Sinai has also limited people’s opportunities and resources. Numerous Sinai inhabitants have been subjected to indiscriminate attacks by the state as well as forced evictions.

At the same time, the nature of the attack is highly difficult to control because of physical and geographical challenges. But is it possible to divorce the state’s responsibility from physical security challenges? Is it possible to view the terror incidents in isolation of the context created by state policies and actions?

Incompetent or intentional?

Is the failure intentional or a result of general incompetence that is ever present in Egypt’s institutions? This question is also up for discussion and not easily resolvable. While policies are far from perfect, it is unlikely that they are carried out efficiently.

The present practices are demonstrably doing more harm than good. Is it possible that the Egyptians are unaware of this? Or is it simply, when all you have is a hammer all your problems look like a nail?

The argument for incompetence is a strong one since Egyptian security forces are poorly trained and the top brass often resort to rhetoric revolving around conspiracy theories, such as fourth-generation warfare, as a scapegoat for their failures.

It is also widely known that incompetence permeates all segments of the Egyptian government, and the military and police are not immune.

However, the intentionality of maintaining a state of crisis when it comes to terrorism is not without merits.

Sisi’s mandate came from fighting terrorism rather than elections. At a time where extremism is a threat to the entire world with the rise of the Islamic State, world leaders have been happy to turn a blind eye towards any rights abuses in exchange for a proxy to help them fight extremists.

With poor political and economic performance, the continued threat of terror becomes the raison d’etre for Sisi’s rule.

Indeed, before rising to power, Sisi displayed an accurate understanding that violent policies such as those adopted by his regime can only lead to increased violence and alienation of the north Sinai population. He understood that forced evictions and indiscriminate targeting of north Sinai residents would create violence.

Islamic State prisoners find ample opportunity within Egyptian prisons to recruit. Enforced disappearances are common in north Sinai.

When speaking to Nabil Elboustany following his release after being forcibly disappeared by the army in 2015, he recounted his experience in the Azouli prison in Ismaileya. He described how hundreds or maybe even thousands of north Sinai residents were being forcibly disappeared by the army, mistreated and then released.

Elboustany’s testimony was recently echoed by Ibrahim Halawa an Irish citizens who spent four years in jail before being acquitted. Halawa witnessed the radicalization inside prisons and the strong growth of the Islamic State within its walls.

The questions surrounding the climate of extremism and violence in Egypt are important to understand what may need to be done if a more competent and less obstinate administration were to tackle the problems of extremism and terrorism.

Until then, more will suffer the consequences of the current context and many will be caught between the proponents of brute force.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of MuslimVillage.com.