By: Andrea Teti and Pamela Abbott

Source: openDemocracy

Findings from the Arab Transformation survey carried out in 2014 in six developing Arab states, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia suggest that the EU assumption of democratisation as a value shared with Arab states is misplaced. Few respondents wanted the EU brand of ‘thin’, procedural democracy in which civil and political rights remain decoupled from social and economic rights. Furthermore, few respondents thought the EU had done a good job of facilitating a transition to democracy in their country or had much appetite for EU involvement in the domestic politics of their countries.

The EU, like other western powers, was quick to portray the 2011 uprisings as a popular demand for liberal democracy – procedural democracy and political rights. However, while the uprisings were intensely political, a demand for regime change, they were not primarily a demand for democratisation, or at least for the ‘thin’ definition promoted by the EU.

Protesters were more concerned about social justice, economic security and employment. In response to the uprisings, the EU revised its policies and claimed that it would encourage ‘deep democracy’. It also promised to listen to Arab voices. However, analysis of policy documents reveals that the EU model of democracy remained substantively unchanged and did not respond to popular demands for social justice and economic rights.

In particular, it systematically underestimates not only the role of social justice and economic rights in sustaining and ‘deepening’ democracy but also the importance of inclusive economic development for security. Democracy without inclusive economic growth is not going to prevent conflict in the region. Furthermore, the EU continues to cooperate with authoritarian regimes on democracy and human rights rather than trying to establish the domestic conditions for democratisation.

By 2014, when the Arab Transformations survey took place, out of the six countries covered only Tunisia was on a path to democracy. The economic and social conditions that drove the 2011 uprisings had if anything deteriorated, with high unemployment and worsening social inequalities. While most citizens who were surveyed agreed that ‘democracy as a system may have its problems but is better than other systems’, the proportion that strongly agreed with this proposition was much lower – as low as 18% in both Tunisia and Iraq.

Meanwhile, a majority disagreed that democracy and Islam were incompatible. There is relatively strong support for the view that there should be a separation between politics and religion, ranging from nearly three quarters in Egypt to 49 per cent in Morocco. However, in Libya, Morocco and Jordan a narrow majority prefer a religious party. And there is considerable variation between the six countries when it comes to the extent that all laws should be based on Shari’a, varying from two-thirds of people thinking this should be the case in Libya to just 17 per cent in Tunisia. The surprisingly low support for democracy in Tunisia – the one country that has moved from an anocracy to a democracy since 2011 – is probably a reflection of both the heightened expectations and fractious reality since the fall of Ben Ali.

However, there is strong support across the region, although somewhat lower in Tunisia, for all family, criminal and property law being based on Shari’a. Support is highest in Jordan and Libya, with over 90 per cent of people supporting it for all three types of law. In Iraq over 90 per cent support it for family law and property law and in Egypt and Morocco over 80 per cent, with between 50 and 60 per cent supporting it for criminal law. Even in Tunisia 78 per cent support Shari’a as a basis for inheritance law, 60 per cent for family law and 33 per cent for criminal law. Support for non-Muslims having fewer political rights than Muslims varies across the countries from a high of 50 per cent in Libya to a low of 11 per cent in Egypt; 13 per cent support ths in Iraq, 16 per cent in Tunisia, 20 per cent in Morocco and 42 per cent in Jordan.

So what political system do they want?

The Arab countries do not necessarily want the type of liberal democracy promoted by the EU; people are open to more than one type of government being suitable for their country, and there is relatively strong support for other systems in some countries. This is likely to be at least in part because they have been told for years by authoritarian rulers that they have democracy already because they have the right to vote in elections. Yet few people think that elections are completely free and fair in their country, with the notable exception of Tunisia, and even here only 59 per cent do so.

What, then, do people in the six countries think about when they say that democracy is the best system despite its faults?

Providing for the welfare of citizens – inclusive development, the provision of basic services and full employment – is seen as important by a majority of citizens, varying from nearly two thirds in Morocco to half in Libya. Inclusive growth and the provision of basic services are both seen as important by a sizable minority and full employment is also nominated by a noticeable minority of respondents. In Iraq and Jordan over 40 per cent of citizens think that a democracy fights corruption, as do a noticeable minority in the other countries.

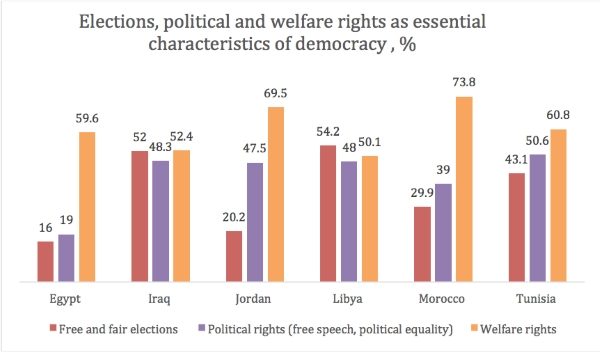

However, in all countries a significant proportion of people include welfare rights as essential characteristics of democracy and they are mentioned more frequently than elections or political rights in all countries with the exception of Libya and very noticeably so in Egypt, Jordan and Motocco. What does emerge quite clearly is that there is no strong demand for procedural democracy as promoted by the EU. In general, Arab citizens are much more concerned about the economic situation, corruption and inequalities, and in the case of Iraq and Libya also security, than they are about authoritarianism. When people in MENA say that democracy is the best system despite its faults or that it is suitable for their country, it is not a political system they have in mind but a way of life. MENA citizens would like to live decent lives in decent societies, with good economic and welfare support and freedom to engage in politics, if they wish to do so, without fear of arrest, assault or social exclusion. The two sides of their image of the decent society are related to each other insofar as lack of resource and access to necessary goods, services and support excludes people from the society of their fellow citizens.

To the extent that European countries, which are democracies of various kinds, are able to offer their citizens decent life-opportunities, they are role models to be copied, but the precise way in which they select their governments is not the most important thing about them.

This has two consequences. The first, already recognised in European policy, is the need to work with non-state civil society organisations as well as with governments. This may entail training the populace in advocacy for their own positions and their critique of government policy, which will not endear Europe to governments, but it is the only way to change values sustainably. The EU can establish common ground with MENA partners by focusing on the main concerns of citizens – an economic order that is more just and less corrupt and guarantees socio-economic rights.

When it becomes an issue of EU aid and support, all countries prefer financial aid – to create jobs, to train people for them or more generally to support education, health etc. There is little appetite for explicit or direct interference in national policy, and they are not impressed so far by the EU’s influence on democratisation.

See the full briefing in The Arab Transformations Policy Briefs. No.1 from the University of Aberdeen.

Andrea Teti is Director of the Centre for Global Security and Governance at the University of Aberdeenand Senior Fellow at the Brussels-based European Centre for International Affairs. Follow him on Twitter @a_teti.

Pamela Abbott is Honorary Professor of Sociology at the University of Aberdeen, and co-author of The Decent Society; planning for social quality, Routledge, 2016.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of MuslimVillage.com.