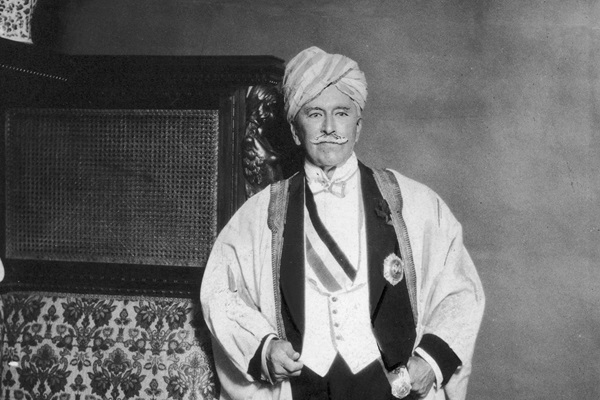

'It is possible that some of my friends may imagine that I have been influenced by 'Mohammedans'; but it is not the case, for my convictions are solely the outcome of many years of thought,' Lord Headley, who adopted the name Sheikh Rahmatullah al-Farooq, said of his conversion to Islam in 1913 [Getty]

!['It is possible that some of my friends may imagine that I have been influenced by 'Mohammedans'; but it is not the case, for my convictions are solely the outcome of many years of thought,' Lord Headley, who adopted the name Sheikh Rahmatullah al-Farooq, said of his conversion to Islam in 1913 [Getty]](https://muslimvillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Lord-Headley-600x400.jpg)

Source: Al Jazeera

London, UK – When Londoners elected Sadiq Khan as mayor of their city, it sparked fresh debate about the place of Islam and Muslims in Britain.

Khan became one of the most popular Muslim politicians in Europe when he won 57 percent of the votes in London’s mayoral election as his Conservative opponent, Zac Goldsmith, faced accusations of running a divisive campaign.

Today, Britain has a large and diverse Muslim population with just over 2.7 million Muslims living in England and Wales.

In the late Victorian era, Britain presided over a vast empire in the East, which included millions of Muslims. When some of the most privileged sons and daughters of that empire embraced Islam, it was met less with hostility than mild curiosity and slight bemusement.

In 1913, the Daily Mirror newspaper responded to Lord Headley’s conversion in a story headlined “Irish peer turns to Islam”.

“That the lure of Eastern religions is affecting an increasing number of Europeans, is again shown by the announcement that Lord Headley, an Irish peer, who spent many years in India, has become a convert to Islam,” the article stated.

Like Headley, many of the early British converts to the religion were young aristocrats or the children of the mercantile elite. Some were explorers, intellectuals and high-ranking officials of empire who had worked and lived in Muslim lands under British colonial rule.

The stories of these converts, says Professor Humayun Ansari of Royal Holloway, University of London, reflect the turbulent times in which they lived, as well as the profound questions that were being raised about religion and the nature and origins of humanity.

“There was the carnage and chaos of the First World War, the suffragette movement, the questioning of imperialism and the right of the British and other Western empires to rule over vast numbers of people,” says Ansari. “In many ways, [those who converted] were living in a very troubled world. In Britain’s wars in Sudan and Afghanistan, and later Europe, they saw terrible slaughter, with armies and governments on all sides claiming God was with them.

“They had experienced what they saw as the peace, the spirituality and simplicity of Islamic societies, and it appealed greatly to them,” Ansari adds.

These stories point to an era when Islam could be seen in a far different light in the West than it often is today. These scholars, travellers and spiritual explorers could, in what were times of great upheaval and conflict, look to the East and see in the Islamic faith a religion which one convert, Lord Headley, characterised as being of “peace, brotherhood and universal values”.

They may be figures of a now distant era. But their personal journeys and their quests to understand Islam and the East reveal how questions and conflicts we may see as unique to our times were, in fact, being raised over a century ago.

Here are the stories of some of Britain’s Victorian Muslims:

!['When we consider that Islam is so much mixed up with the British Empire, and the many millions of Muslim fellow subjects who live under the same rule, it is very extraordinary that so little should be generally known about this religion. And consequently the gross ignorance of the masses on the subject allows them to be easily deceived, and their judgement led astray,' said Abdullah Quilliam on Islam and the British Empire [Archive]](https://muslimvillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/William-Quilliam-600x400.jpg)

William Quilliam (1856-1932)

One of the first high-profile converts was William (later Abdullah) Quilliam, the son of a prominent Methodist preacher and watch-making magnate in Liverpool. Born a Methodist in 1856, Quilliam converted to Islam in the early 1880s. He had travelled from his native England to Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria when he was 17, seeking a warmer climate to aid his recovery from an illness.

Quilliam became fascinated with the Islamic faith and immersed himself in studying it. He converted in Morocco, returned to Liverpool and began promoting the faith under his adopted name, Abdullah Quilliam.

Still in his 20s and a qualified solicitor, Quilliam founded the first mosque in Britain, which opened on Christmas Day 1889 in Liverpool and, in 1894, he was named leader of Britain’s Muslims by the last Ottoman caliph, Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Quilliam wrote books aimed at introducing the Islamic faith to British people, even sending a copy to Queen Victoria, who is reported to have enjoyed it and asked for several copies for her children.

Quilliam died in London in 1932 and was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking, which has a large Muslim burial ground and is also the final resting place of other prominent Anglo-Muslims.

Lady Evelyn Cobbold (1867-1963)

It was Lady Evelyn, later Zainab, Cobbold who was one of the last of the aristocratic Victorians to convert. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1867, the daughter of the 7th Earl of Dunmore, Lady Evelyn seemed equally at home in the fashionable salons of Mayfair and Paris as in remote camps in the Libyan Desert. She was a noted sportswoman, a deerstalker and a crack shot.

!['My delight was to escape my governess and visit the mosques with my Algerian friends, and unconsciously I was a little Muslim at heart,' wrote Lady Evelyn Cobbold [Archive]](https://muslimvillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Lady-Evelyn-600x400.jpg)

When she died in 1963 at the age of 96, she left instructions that her gravestone, on a hill in remote Inverness in Scotland, bear the words: “Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth.”

She spent much of her childhood in Algiers and Cairo, where she was raised with Muslim nannies, and later wrote about how she felt to be Muslim from as early as she could remember, but only decided to profess her faith during a personal audience with the Pope. She recounted the meeting in Pilgrimage To Mecca:

“Some years went by, and I happened to be in Rome staying with some Italian friends when my host asked if I would like to visit the Pope. Of course, I was thrilled. When His Holiness suddenly addressed me, asking if I was a Catholic, I was taken aback for a moment and then replied that I was a Muslim. What possessed me I don’t pretend to know, as I had not given a thought to Islam for many years. A match was lit, and I then and there determined to read up and study the faith.”

Rowland Allanson-Winn, 5th Baron Headley (1855-1935 – pictured above)

Rowland Allanson-Winn, better known as Lord Headley, would have been the first Muslim to sit in the House of Lords had he taken the position due to him when he became the 5th Baron Headley in 1913. That same year, instead, he converted to Islam and became Shaikh Rahmatullah al-Farooq. One year later, in 1914, Lord Headley headed the British Muslim Society.

Born in London in 1855 and educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, Lord Headley had been brought up as a Protestant before studying Roman Catholicism while living on the family’s ancestral estate in Ireland. An accomplished engineer, early pioneer of martial arts, traveller and journalist, the Anglo-Irish aristocrat was considered a Victorian Renaissance man. He first encountered Islam in Kashmir in the mid-1890s while working for the British Raj in India.

He came to see Islam as a religion of tolerance and studied the faith in England with his mentor, the prominent Indian lawyer and Islamic scholar Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, before World War I.

Lord Headley was, by all accounts, an eccentric. One contemporary profile published in Time Magazine described him as “a man of many parts, a champion middleweight boxer in his day at Cambridge, a distinguished globe-trotter, an editor and excellent raconteur”.

He was also one of the earliest exponents of what we know today as martial arts. In 1890, Lord Headley co-wrote one of the earliest manuals on self-defence called Broad-sword and Singlestick, before going on to write one of the first modern guides to boxing.

He made the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in 1923.

As he lay dying in England in June 1935, he scribbled a note to his son, his final request being that he be buried in an Islamic cemetery.

Marmaduke Pickthall (1875-1936)

Muhammed Marmaduke Pickthall was an English scholar, born to an Anglican clergyman. Before converting, Pickthall travelled widely, studying and working across India and the Middle East.

!['Each man must see with his own eyes and not another’s. People are as one finds them, good or bad. They change with each man’s vision, yet remain the same,' Muhammed Marmaduke Pickthall wrote of what he had learned during his travels to the Middle East[Archives]](https://muslimvillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Marmaduke-Pickthall-600x400.jpg)

He was also a successful novelist, counting D H Lawrence, H G Wells and E M Forster among his admirers. He converted to Islam in 1917 and went on to publish a modern English translation of the Quran, which was later authorised by the famous Azhar University in Cairo and which remains a standard work to this day. When he published his translation, the Times Literary Supplement praised the work as “a great literary achievement”.

In the foreword to his translation, which he titled The Meanings of the Glorious Quran, Pickthall wrote: ” … The Quran cannot be translated ….The book is here rendered almost literally and every effort has been made to choose befitting language. But the result is not the Glorious Quran, that inimitable symphony, the very sounds of which move men to tears and ecstasy. It is only an attempt to present the meaning of the Quran and peradventure something of the charm in English. It can never take the place of the Quran in Arabic, nor is it meant to do so ….”

As a schoolboy at Harrow Public School, Pickthall was a classmate and friend of Winston Churchill. A gifted linguist, he mastered several languages, including Arabic, and came to see himself as no longer an Englishman, but a Muslim “of the East”.

He died in Cornwall in 1936 and was buried in the Muslim cemetery at Brookwood in Surrey, England.

Source: Al Jazeera