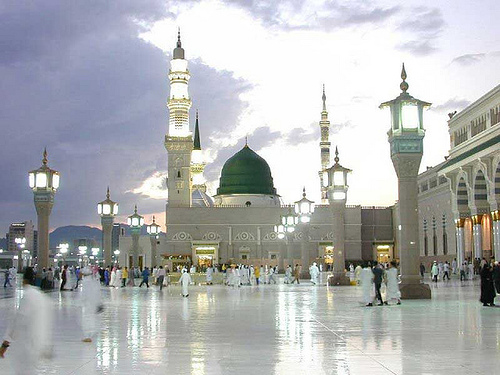

Three of the world’s oldest mosques are about to be destroyed as Saudi Arabia embarks on a multi-billion-pound expansion of Islam’s second holiest site. Work on the Masjid an-Nabawi in Medina, where the Prophet Mohamed is buried, will start once the annual Hajj pilgrimage ends next month. When complete, the development will turn the mosque into the world’s largest building, with the capacity for 1.6 million worshippers.

But concerns have been raised that the development will see key historic sites bulldozed. Anger is already growing at the kingdom’s apparent disdain for preserving the historical and archaeological heritage of the country’s holiest city, Mecca. Most of the expansion of Masjid an-Nabawi will take place to the west of the existing mosque, which holds the tombs of Islam’s founder and two of his closest companions, Abu Bakr and Umar.

Just outside the western walls of the current compound are mosques dedicated to Abu Bakr and Umar, as well as the Masjid Ghamama, built to mark the spot where the Prophet is thought to have given his first prayers for the Eid festival. The Saudis have announced no plans to preserve or move the three mosques, which have existed since the seventh century and are covered by Ottoman-era structures, or to commission archaeological digs before they are pulled down, something that has caused considerable concern among the few academics who are willing to speak out in the deeply authoritarian kingdom.

“No one denies that Medina is in need of expansion, but it’s the way the authorities are going about it which is so worrying,” says Dr Irfan al-Alawi of the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation. “There are ways they could expand which would either avoid or preserve the ancient Islamic sites but instead they want to knock it all down.” Dr Alawi has spent much of the past 10 years trying to highlight the destruction of early Islamic sites.

With cheap air travel and booming middle classes in populous Muslim countries within the developing world, both Mecca and Medina are struggling to cope with the 12 million pilgrims who visit each year – a number expected to grow to 17 million by 2025. The Saudi monarchy views itself as the sole authority to decide what should happen to the cradle of Islam. Although it has earmarked billions for an enormous expansion of both Mecca and Medina, it also sees the holy cities as lucrative for a country almost entirely reliant on its finite oil wealth.

Heritage campaigners and many locals have looked on aghast as the historic sections of Mecca and Medina have been bulldozed to make way for gleaming shopping malls, luxury hotels and enormous skyscrapers. The Washington-based Gulf Institute estimates that 95 per cent of the 1,000-year-old buildings in the two cities have been destroyed in the past 20 years.

In Mecca, the Masjid al-Haram, the holiest site in Islam and a place where all Muslims are supposed to be equal, is now overshadowed by the Jabal Omar complex, a development of skyscraper apartments, hotels and an enormous clock tower. To build it, the Saudi authorities destroyed the Ottoman era Ajyad Fortress and the hill it stood on. Other historic sites lost include the Prophet’s birthplace – now a library – and the house of his first wife, Khadijah, which was replaced with a public toilet block.

Neither the Saudi Embassy in London nor the Ministry for Foreign Affairs responded to requests for comment when The Independent contacted them this week. But the government has previously defended its expansion plans for the two holy cities as necessary. It insists it has also built large numbers of budget hotels for poorer pilgrims, though critics point out these are routinely placed many miles away from the holy sites.

Until recently, redevelopment in Medina has pressed ahead at a slightly less frenetic pace than in Mecca, although a number of early Islamic sites have still been lost. Of the seven ancient mosques built to commemorate the Battle of the Trench – a key moment in the development of Islam – only two remain. Ten years ago, a mosque which belonged to the Prophet’s grandson was dynamited. Pictures of the demolition that were secretly taken and smuggled out of the kingdom showed the religious police celebrating as the building collapsed.

The disregard for Islam’s early history is partly explained by the regime’s adoption of Wahabism, an austere and uncompromising interpretation of Islam that is vehemently opposed to anything which might encourage Muslims towards idol worship.

In most of the Muslim world, shrines have been built. Visits to graves are also commonplace. But Wahabism views such practices with disdain. The religious police go to enormous lengths to discourage people from praying at or visiting places closely connected to the time of the Prophet while powerful clerics work behind the scenes to promote the destruction of historic sites.

Dr Alawi fears that the redevelopment of the Masjid an-Nabawi is part of a wider drive to shift focus away from the place where Mohamed is buried. The spot that marks the Prophet’s tomb is covered by a famous green dome and forms the centrepiece of the current mosque. But under the new plans, it will become the east wing of a building eight times its current size with a new pulpit. There are also plans to demolish the prayer niche at the centre of mosque. The area forms part of the Riyadh al-Jannah (Garden of Paradise), a section of the mosque that the Prophet decreed especially holy.

“Their excuse is they want to make more room and create 20 spaces in a mosque that will eventually hold 1.6 million,” says Dr Alawi. “It makes no sense. What they really want is to move the focus away from where the Prophet is buried.”

A pamphlet published in 2007 by the Ministry of Islamic Affairs – and endorsed by the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, Abdulaziz al Sheikh – called for the dome to be demolished and the graves of Mohamed, Abu Bakr and Umar to be flattened. Sheikh Ibn al-Uthaymeen, one of the 20th century’s most prolific Wahabi scholars, made similar demands.

“Muslim silence over the destruction of Mecca and Medina is both disastrous and hypocritical,” says Dr Alawi. “The recent movie about the Prophet Mohamed caused worldwide protests… and yet the destruction of the Prophet’s birthplace, where he prayed and founded Islam has been allowed to continue without any criticism.”

Mecca and Medina in numbers

12m – The number of people who visit Mecca and Medina every year

3.4m – The number of Muslims expected to perform Hajj (pilgrimage) this year

60,000 – The current capacity of the Masjid an-Nabawi mosque

1.6m – The projected capacity of the mosque after expansion

RELATED:

Mecca’s mega architecture casts shadow over hajj

by Oliver Wainwright

Source: guardian.co.uk

A glowing green disc hovers high in the sky at night, casting an eerie glow over a forest of minarets, cranes and concrete frames that seem to stretch endlessly into the dusty distance, like a vast field of dominoes. The disc is the largest clockface in the world – and not only does it adorn the tallest clocktower in the world, it also sits atop a building boasting the biggest floor area in the world. Visible 30km away, this is the Abraj al-Bait, which rises like Big Ben on steroids to tower 600m over the holy mosque of Mecca in the spiritual heart of the Islamic world.

This thrusting pastiche palace houses an array of luxury hotels and apartments, perched above a five-storey slab of shopping malls. Completed last year at a cost of $15bn (£9bn), it stands where an Ottoman fortress once stood. A stone citadel built in 1781 to repel bandits, the Ajyad fortress’s demolition sparked an international outcry in 2002, but this was quickly rebuffed by the Saudi Islamic affairs minister. “No one has the right to interfere in what comes under the state’s authority,” he said. “This development is in the interest of all Muslims all over the world.” The fortress wasn’t just swept away – the hill it sat on went, too.

Shooting 26 searchlights 10km into the skies, and blaring its call to prayer 7km across the valley, the Abraj al-Bait is also the world’s second tallest building. Encrusted with mosaics and inlaid with gold, it is the most visible (and audible) sign of the frenzied building boom that has taken hold of Saudi Arabia’s holy city over the last 10 years. “It is truly indescribable,” says Sami Angawi, architect and founder of the Jeddah-based Hajj Research Centre, who has spent the last three decades researching and documenting the historic buildings of Mecca and Medina, few of which now remain. In particular, the house of the prophet’s wife, Khadijah, was razed to make way for public lavatories; the house of his companion, Abu Bakr, is now the site of a Hilton hotel; and his grandson’s house was flattened by the King’s palace. “They are turning the holy sanctuary into a machine, a city which has no identity, no heritage, no culture and no natural environment. They’ve even taken away the mountains,” says Angawi.

Geological features have proved no match for dynamite and concrete, which are being liberally deployed to make way for the burgeoning number of visitors. Three million Muslims arrived in Mecca this week for the annual hajj pilgrimage, an event that has mutated from a simple, spartan rite of passage, in which pilgrims give up their worldly goods, into a big-bucks business worthy of Las Vegas – with the overblown architecture to match.

Along the western flank of the city are the first towers of the Jabal Omar development, a sprawling complex that will eventually accommodate 100,000 people in 26 luxury hotels – sitting on another gargantuan plinth of 4,000 shops and 500 restaurants, along with its own six-storey prayer hall. The line of blocks, which will climb to heights of up to 200 metres and terminate in a monumental gateway building, share the clocktower’s Islamic-lite language: a cliched dressing of pointed arches and filigree grillwork plastered over generic concrete shells.

The developers have somehow transformed a type of architecture that evolved from a dense urban grain of low-rise courtyards and narrow streets into meaningless wallpaper: an endlessly repeatable pattern for the decoration of standardised slab after standardised slab. Flimsy rows of concrete arches hang above swaths of blue mirror glass, punctuated by stick-on timber trellis screens. These are modelled on traditional mashrabiya panels, those beautiful latticework openings designed as ventilating veils, but here they become meaningless applique. “If we are imitating, why can’t we imitate the best?” asks Angawi, in a tone of desperation. “Why are we imitating the worst mistakes of 60 or 70 years ago from around the world – only even bigger?”

Another development of repetitive slabs, echoing Jabal Omar’s toast-rack urbanism, is slated for the northern side of the Grand Mosque, at al-Shamiya, while a $10bn plan to provide an extra 400,000 sq metres of prayer halls there is almost complete. Standing like a gigantic triangular slice of wedding cake, this building will accommodate 1.2m more worshippers each year, but it has come at a price.

“This was the most historic part of the old city,” says Irfan al-Alawi, executive director of the UK-based Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, who has worked in vain to raise the profile of his country’s historic sites. “It has now all been flattened.” Residents were evicted, he says, with one week’s notice, and many have still not been compensated – a common story across Mecca’s developments. “They are now living in shantytowns on the edge of the city without proper sanitation. Locals, who have lived here for generations, are being forced out to make way for these marble castles in the sky.”

Alawi describes the imminent arrival of yet more seven-star hotels even closer to the mosque than the al-Bait clocktower, as well as proposals to develop Jabal Khandama, on the hills to the east, which will likely see the erasure of the site where the prophet Muhammad was born. Alawi says this wilful destruction of Islamic heritage is no accident: it is driven by state-endorsed wahhabism, the hardline interpretation of Islam that perceives historical sites as encouraging sinful idolatry. So anything that relates to the prophet could be in the bulldozer’s sights.

“It is the end of Mecca,” says Alawi. “And for what? Most of these hotels are 50% vacant and the malls are empty – the rents are too expensive for the former souk stall-holders. And people praying in the new mosque extension will not even be able to see the Kaaba.”

The Kaaba is the holy black cube in the centre of the Grand Mosque, around which pilgrims walk; proximity to it has become the ultimate currency, allowing hotel suites with the best views to charge $7,000 per night during peak seasons. This unique concentricity, with everything determined by its orientation towards the hallowed centre, has spawned a strangely diagrammatic radial urbanism. From above, like a sea of iron filings pulled by a magnet, the whole city appears to crowd round a core, the vortex of pilgrims giving way to an equally swirling current of tower blocks. It is the axis of prayer writ large in concrete.

The road to Mecca funnels traffic into two lanes: the one marked “Muslims only” goes to the holy city; the other, marked “Non Muslims”, bypasses it, since the latter – me included – are forbidden entry to Mecca (and Medina) under Saudi law. Soon after this hajj, work will start on the expansion of the mataf, the open area around the Kaaba, to triple its capacity to 130,000 pilgrims per hour. But to create this, the historic centre of the mosque will be obliterated. “They want to get rid of the brick vaults and stone columns that have stood there since the 17th century,” says Alawi. “These are the oldest part of the holy mosque, designed by the great architect Sinan. The pillars are inscribed with stories and the names of the prophet’s companions, so the wahhabis want to see them bulldozed.”

The desperation to be, or feel, as close as possible to the Kaaba has forced buildings to become ever higher, ever more ridiculously tapered, so everyone can have a view, however notional, of the sacred centre. This has given the sanctified “mother of villages” the most expensive real estate in the world: a square foot around the Grand Mosque now sells for up to $18,000, mayor Osama al-Bar said last year, dwarfing the Monaco average of $4,400.

As the influx of pilgrims increases, land values will continue to rise: 12 million visit the city every year, a figure expected to swell to 17 million by 2025. They will be eased on their way by a new high-speed rail link that will connect gateway city Jeddah with Mecca and Medina. Jeddah’s King Abdul Aziz international airport is itself undergoing expansion to quadruple its capacity to 80 million passengers a year.

Fuelled by petrodollars, all of these vast projects are now either completed or well under way. So it seems strange that King Abdullah should only now be ordering the creation of a masterplan for Mecca and its surroundings, covering buildings, transport and infrastructure – given that most of the city’s holy mountains have been dynamited into dust, and all but a handful of its ancient monuments buried beneath soaring structures. As Angawi says: “There is no other place in the world where development starts with bulldozing before planning. But it is not too late if we stop now. Otherwise, we risk the sanctity of Mecca being gone for ever.”

Prayer room with a view: a pilgrim’s perspective

Everything about the hajj is overwhelming – the numbers, the logistics, the infrastructure, the stakes – so it’s no surprise that the architecture is catching up. Its sleek and state-of-the-art towers offer butler services, designer toiletries, entire floors reserved for Saudi royalty, wet rooms, helipads, quality linens, plush carpets and thick bathrobes.

During my 2010 visit to Mecca, a number of hotels in the Abraj al-Bait complex were at 100% capacity. The hotel employee showing me around one presidential suite said I could pray in front of the Qibla without ever leaving the room, gesturing to a window with priceless views to prove his point. The sense of exclusivity extended to the reservation system, too. Rooms could only be booked through the hotel, but not as part of a package, the traditional if not the uniform way of securing accommodation in Mecca.

None of this is visible at ground level. Pilgrims occupy every available space and the dimensions of the projects are too grand to be appreciated simply by craning the neck. Instead, the best views are from the Jeddah-Mecca Highway, where the clocktower appears to rear out of the barren landscape in such an outlandish fashion it looks as if it has been drawn on to the skyline. The vast floor-to-ceiling windows of al-Safa Palace, perched on a hill above Mecca’s holy sites, fully reveal the audacious vision to reshape the pilgrimage.

The building work has inevitably changed the hajj experience for everyone. Aside from the increased pollution and heavy machinery, there is more segregation along economic and class lines. Muslims cannot choose where or when to perform the hajj – it can only be done in Mecca, at a certain point in the year – but they can choose where to stay.