By: Shafik Mandhai & Ayseba Umutlu

Source: Al Jazeera

When Kerim Ture placed his first order for a batch of long-sleeved tunics that could be worn by Muslim women, the manufacturers producing them demanded payment upfront, apparently convinced the venture would fail and Ture would be left unable to pay them.

The Turkish entrepreneur quickly proved that their scepticism was unfounded, and he was back shortly afterwards to place a new order, having sold the first.

Today the website Ture established to sell his products, Modanisa, attracts 100 million visitors annually, has customers in 120 countries, and has no shortage of manufacturers willing to work with it.

“Modanisa now has 300 suppliers and 30 designers, it’s become a platform for hundreds of suppliers from all over the world who want to sell products on our site,” a spokesperson for the company told Al Jazeera.

However, Ture’s story is not simply about one company’s success and his own financial achievements.

In establishing Modanisa in 2011, Ture wanted to offer Muslim women who chose to adopt “modest” Islamic dress codes, more options than were then available and give them an outlet they had lacked.

“Just because they (Muslim women) wanted to cover a little more, the world ignored them and they had to suffer with the same old boring clothes,” Ture told the audience at a TEDx talk in Bulgaria in May, adding: “We thought it was unfair.

“Clothing is more than a fabric you put on your body, it’s more than that, it’s part of your expression and part of your identity, it’s unfair.”

Modanisa is one small part of the diverse and expanding ‘halal’ sector, which according to research by the Thomson Reuters foundation is estimated to be worth $3.7 trillion by 2019.

As ‘halal’ simply means ‘permissible’ in the Arabic language, the term can be applied to any product or service, which does not violate Islamic laws and social norms.

What separates halal industries from others, which do not necessarily fall foul of Islamic injunctions, is a conscious effort to accommodate the requirements of Muslim consumers.

The industries involved are as varied as banks offering services that avoid the accrual of interest and nail varnish that allows a user to perform ablution before prayer.

Other major industries include the halal food sector, clothing, and tourism.

The trend is particularly noticeable among Muslim communities in western countries, such as the UK, where international brands such as KFC and Subway offer halal menus, clothes shops such as H&M and Marks and Spencer sell clothing lines geared towards Muslim women, supermarkets have halal food sections, and mainstream banks offer Islamic finance products.

Cardiff University’s Dr Jamal Ahmed explained that consumption of ‘halal’ products was driven just as much by issues of identity as commitment to Islamic rules.

“Academic studies have consistently reported that ethnic minorities in general but Muslims in particular, feel more strongly about their identities than people back home (their countries of origin),” Ahmed said.

“Accordingly, Muslims seek identity anchors when they construct their notions of self and make a statement about who they are.

“Consuming halal, be it food, clothing, travel or Islamic finance, gives them a sense of identity but also a sense of stability and freedom from anxieties.”

However, where an individual consumer sees the fulfilment of a religious obligation or act affirming their identity, governments see fiscal growth potential.

Recent exhibitions of halal businesses in Japan and Turkey drew backing from the governments of those countries.

In 2013, former British Prime Minister David Cameron declared his intent to make London “one of the great capitals of Islamic finance“, and announced the issue of the UK’s first government bond compliant with Islamic law, becoming the first non-Muslim state to do so.

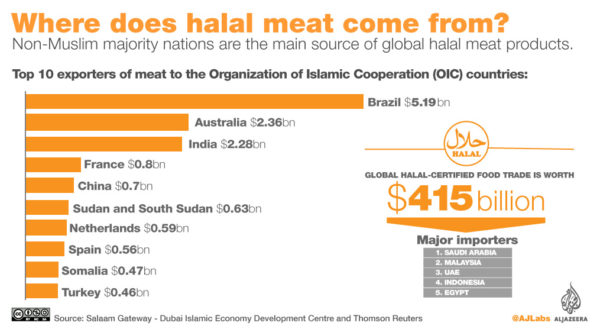

It’s not just in the financial industry that countries that are not majority-Muslim are taking a lead role in the growth of the halal sector.

Brazil’s Muslims make up a tiny part of its population of 207 million people, at just over 200,000, yet the country is a leading exporter of halal beef, with the industry valued at close to $6bn in 2015.

Similarly, New Zealand is also a leading exporter of halal meat despite its relatively small Muslim population, with sales of $576m.

Abdul Azim Ahmed, a researcher in Contemporary Religion, told Al Jazeera that while the growth in the halal sector gave accessible alternatives to the Muslim population, there was also a danger of “simply reducing Muslim ethics down to consumer choice”.

Ahmed explained that placing too much emphasis on the consumer end of halal produce, took the focus away from the wider issue of whether aspects such as the manufacturing processes or treatment of workers complied with Islamic ethics.

“The greater accessibility of halal meat is certainly a good thing in democratising food, there is still however a question to whether or not industrial scale slaughter of animals meets the spirit of Islamic ethics.”

“Another example, the Nike ‘Pro-Hijab’ was chosen as one of 2017’s top inventions by Time Magazine. The Nike Pro Hijab had negible impact on the lives of Muslim women, and with allegations of abusive work practices still surrounding its many factories, it is right to ask how ‘Islamically’ ethical are the products being pitched at Muslims.

“I believe a truly Islamic approach to business, manufacturing, and conservation requires a fundamentally more radical approach involving governments and transnational organisations, and that it will not be achieved by a shift in consumer practice.”