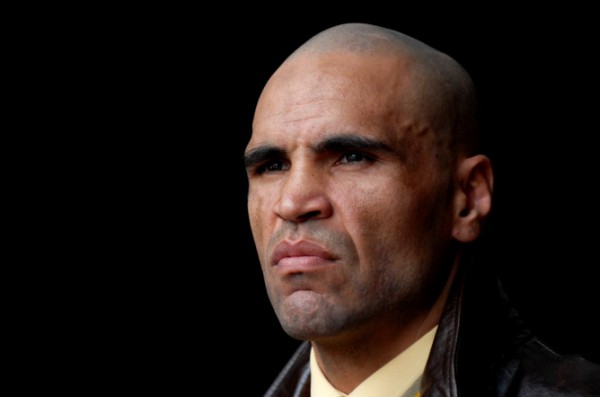

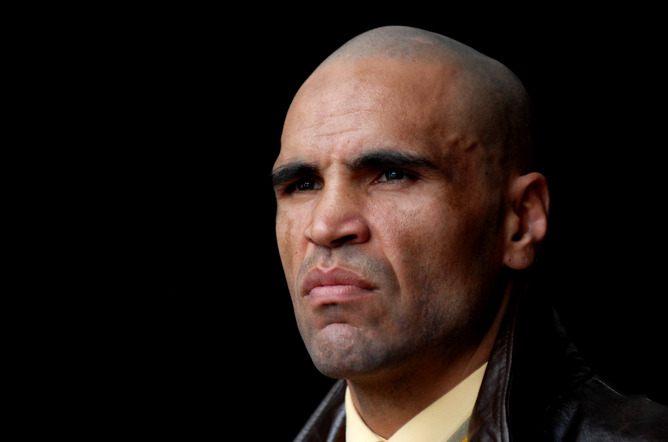

Muslim conversion is growing in Indigenous communities.

In the 2001 national census, 641 Indigenous people identified as Muslim. By the 2006 census the number had climbed by more than 60% to 1014 people.

This recent rise in conversions among Indigenous Australians may seem to be a political gesture. But unknown to many is the long history between Aboriginal people and Islamic culture and religion.

Three centuries of history

Indigenous and Muslim communities have traded, socialized and intermarried in Australia for three centuries.

From the early 1700s, Muslim fishermen from Indonesia made annual voyages to the north and northwestern Australian coast in search of sea slugs (trepang). The trade that developed included material goods, but the visitors also left a lasting religious legacy.

Recent research confirms the existence of Islamic motifs in some north Australian Aboriginal mythology and ritual.

In mortuary ceremonies conducted by communities in Galiwinku on Elcho Island today, there is reference to Dreaming figure Walitha’walitha, an adaptation of the Arabic phrase Allah ta’ala (God, the exalted).

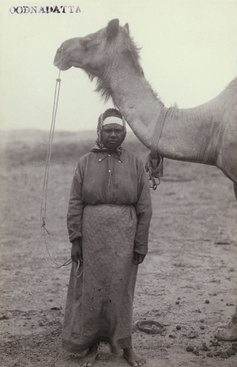

The first Muslims to settle permanently in Australia were the cameleers, mainly from Afghanistan. Between the 1860s and 1920s, the Muslim camelmen worked the inland tracks and developed relationships with local Aboriginal people. Intermarriage was common and there are Aboriginal families with surnames including Khan, Sultan, Mahomed and Akbar.

The first Muslims to settle permanently in Australia were the cameleers, mainly from Afghanistan. Between the 1860s and 1920s, the Muslim camelmen worked the inland tracks and developed relationships with local Aboriginal people. Intermarriage was common and there are Aboriginal families with surnames including Khan, Sultan, Mahomed and Akbar.

From the mid-1880s, Muslim Malays came to north Australia as indentured labourers in the pearl-shelling industry.

They, too, formed longstanding relationships with the Indigenous people they met. A significant number married local Aboriginal women, and today there are many Aboriginal-Malay people in the top end of Australia.

A culture in common

My research has found a broad spectrum of Indigenous identification with Islam. It ranges from those who have Afghan and Malay Muslim ancestors, but are not practising Muslims, to those who have no Muslim ancestors, but are strict adherents of the faith.

The Indigenous Muslims I met perceive a neat cultural fit between their traditional Indigenous beliefs and the teachings of Islam. Many hold that in embracing Islam they are simultaneously going back to their Indigenous roots.

They find cultural parallels in the shared practices of male circumcision, arranged marriages, polygyny (a form of marriage in which a man has more than one wife), and the fact that men are usually older than their wives in both Islamic and traditional Indigenous societies.

Interviewee Alinta, for example, finds “Islam connects with [her] Aboriginality” because of a shared emphasis on gendered roles and spheres of influence. “In Islam, men have a clear role and women have a clear role, and with Aboriginal people, that’s how it was too”.

Others commented on the similar attitudes that Muslims and Indigenous people have towards the environment. According to another interviewee, Nazra, “in the Qur’an it tells you very clearly don’t waste what is not needed … and the Aboriginal community is the same. Water and food are so precious you only take what you need”.

Change what you do, not who you are

Indigenous Muslims are also attracted to Islam because it does not subscribe to the kind of mono-culturalism Christian missionaries imposed on Aboriginal people.

The Qur’an states that Allah made human beings into different nations and tribes. These racial and cultural differences, far from being wrong, are a sign from God.

According to Shahzad, another interviewee from the group, Islam doesn’t just say “you’re Muslim, that’s it. It recognises we belong to different tribes and nations. So it doesn’t do what Christianity did to a lot of Aboriginal people, [which] was try and make them like white people.”

Indigenous Australian Muslims (in common with black Britons and African-Americans), understand conversion to Islam as a means of repairing the deep psychological scars they suffer as a people.

But there are also gender-specific reasons why Islam appeals to Indigenous women and men.

Indigenous women have long been stereotyped as sexually available, and they suffer disproportionate levels of sexual abuse. Wearing the hijab is a practical as well as symbolic deterrent to unwanted attention.

As a public expression of the importance Islam accords the family, it also appeals to Indigenous female converts who, against the backdrop of a long history of family break-up, want to offer their children security and stability.

As a public expression of the importance Islam accords the family, it also appeals to Indigenous female converts who, against the backdrop of a long history of family break-up, want to offer their children security and stability.

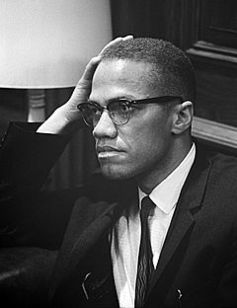

A similarly nuanced set of arguments surrounds the appeal of Islam for Indigenous men. Many, particularly those in the prison system, are initially drawn to Islam through the rhetoric of Malcolm X. But the Islamic notion of “universal brotherhood” and its disavowal of racial distinctions leads to a growth in self-esteem that has a significant influence on the way they think about their roles as husbands and fathers.

Restoring pride and conferring leadership

The attraction of Islam for many Indigenous men is that it recognizes the importance of defined leadership roles for men in their families and communities. These roles have largely been lost through racism and the ongoing legacy of colonization.

As the head of the family, Muslim men have a divine responsibility to protect and maintain their wives and families and this, according to Shahzad, gives him “strength to be a man”.

Many of the men I spoke with identified themselves as former “angry black men”. Incensed by the long history and contemporary reality of racist subjugation of Indigenous Australians, they viewed Anglo-Australian people and society with contempt.

According to one interviewee, Justin: “before I was the typical Black angry man. I was just consumed by anger”.

Sulaiman stressed that he considered terrorism before, not after, becoming a Muslim:

“I could very well have become a terrorist, without Islam, through the way I’ve been treated … Islam came into my life and actually said hey, cool down, it’s alright, justice will be served eventually.”

Rules to live by

Against the backdrop of what Shahzad calls “the hurt of colonisation”, Islam offers Indigenous people an alternative system that includes a strict code of conduct and a moral and ethical framework that, they feel, connects them to their traditional heritage.

For some Aboriginal people, the adoption of a faith that demands the avoidance of alcohol, drugs and gambling has also played a positive role in their lives.

Islam emphasises the equality of all people, regardless of skin colour. For Indigenous men and women, inclusion in the Australian national community has historically depended on the renunciation of their Aboriginality. Membership in an international community that not only tolerates difference, but is predicated on it, can be very empowering.

It is likely that the number of Indigenous Muslims will continue to grow. Indigenous people find that identification with Islam, of whatever kind, meets both their spiritual and social needs – offering a buffer against systemic racism, a clear moral template, well-defined roles and entry to a global society that does not make assimilation the price of admission.