Syrian President Bashar Assad finds himself in the unenviable position reminiscent of the late Libyan leader Moammar Kadafi’s: an autocrat who may fall victim to the shifting geopolitical landscape in an “Arab Spring” that is reshaping the balance of power in the Middle East.

Once a wellspring of Arab pride and nationalism, Syria is confronting the changing dynamics of the region as old alliances fade and new brokers emerge, most notably the tiny emirate of Qatar, which in recent years has boldly challenged traditional powers with a clever mix of wealth and populism through its Al Jazeera network.

Frustrated by Syria’s failure to implement an Arab League peace plan aimed at ending a bloody eight-month crackdown on protests, the Qatar-led alliance on Saturday gave the Assad regime until midweek to come around or face new economic sanctions and a suspension of its membership.

The league had aken such decisive action in only one other Arab Spring uprising, when it voted in March to back a no-fly zone over Libya that contributed to the fall of Kadafi. But Libya was a peripheral partner, not a founding member like Syria — long a deft manipulator of Middle Eastern intrigue, now swept up in geopolitical crosscurrents beyond its control.

On Sunday, Syria’s reeling government put out an “urgent” call to Arab leaders for further talks in the apparent hope of tempering Arab condemnation and forestalling the prospect of foreign intervention in its violent crisis. But the plea came as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, along with a pair of non-Arab nations — Turkey and France — denounced attacks on their diplomatic missions in Syria after the league’s decision.

The diplomatic blow to Syria, long a central player in the Arab League, occurred at a time when Qatar holds the group’s rotating chair and has been pushing for tough action against Syria.

“Qatar is appearing more and more as taking a leading role in the Arab world,” said Randa Habib, a writer and political analyst in Jordan. “It can make the Arab League move.”

Even before facing rejection by the 22-member Arab League, Assad had already lost the support of Syria’s giant and powerful neighbor, Turkey, whose prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, recently extolled the “glorious resistance” of Syria’s antigovernment protesters.

Little Qatar, far away in the Persian Gulf, doesn’t have the physical or military presence of Turkey. But it does have outsized ambitions, diplomatic dexterity, extreme wealth — and the populist force of its Al Jazeera network. Qatar stoked the early days of the Arab Spring and became a leading and sometimes controversial voice for government change in Libya, a role it has now assumed in Syria.

The emirate’s leaders have keenly understood — and certainly benefited from — the changing dynamics reshaping an Arab world unbound from autocrats and suppression.

Qatar is capitalizing on, and Assad is in danger of succumbing to, the most transformative moment in the region since the doomed specter of pan-Arabism of the 1960s. The powers that made up the core of that world have steadily diminished over the years while the oil nations of the Persian Gulf have assumed larger roles in diplomacy, finance and media.

In some respects, Qatar’s influence is eclipsing even that of traditional powers, such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Riyadh has been accused of hypocrisy in its vociferous support for dissidents in Syria while simultaneously helping to crush protests in neighboring Bahrain. Egypt, meanwhile, is consumed with its own political turmoil in the wake of President Hosni Mubarak’s ouster.

Qatar’s ambitions are often larger than regional conflicts and dalliances. To the envy of its neighbors, Doha won the bid to host the 2022 World Cup soccer championship, based partly on an audacious promise to install high-tech air conditioning to cool stadiums during the sweltering gulf summer.

The emirate is adroit at playing all sides: It is home to a U.S. military base, yet it keeps close to the passions of the Arab street through Al Jazeera and maintains cordial relations with Iran, the regional giant just across the gulf.

Saudi Arabia and Iran, meantime, are fierce rivals in a high-stakes regional power struggle. Syria has emerged as a proxy battleground.

Some analysts see Saudi Arabia’s aims in Syria as more linked to geopolitics than human rights. Riyadh blames Shiite-dominated Iran for instigating the rebellion among Shiites in Bahrain and agitating restive Shiites in Saudi Arabia, where Sunnis are in the majority.

Iran’s major Arab ally is Syria, where Assad’s minority Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shiite Islam, holds disproportionate power in a nation where Sunni Muslims are the majority. If the Sunni-led opposition gains control in Damascus, Syria’s putative new leaders may well reject Iran, according to the Saudi calculus, and embrace a new alliance with Riyadh.

The Arab League’s move against Syria on Saturday may signal its transformation from a sleepy bastion for potentates and strongmen to a more dynamic regional alliance.

It is not lost on Damascus that the decision to suspend Syria could also be a precursor to some form of United Nations-approved intervention, as the Arab League endorsed in Libya. The organization did not rule out seeking U.N. help to protect Syrian civilians — perhaps by sending in international monitors, as some opposition activists have demanded.

This is the path that Damascus is now scrambling to avoid, apparently seeking an eleventh hour turnaround before the league suspension becomes final on Wednesday and new economic and political sanctions come into play.

On Sunday, Syria seemed to soften its initial denunciation of the suspension as an illegal product of “U.S.-Western agendas.” The Arab League peace road map — which, among other things, calls for a withdrawal of the Syrian armed forces from populated areas and the beginning of a dialogue with the opposition — still remains “an appropriate frame to resolve the Syrian crisis away from any foreign interference,” the official Syrian Arab News Agency said.

The opposition hailed the Arab League’s censure of Syria as the beginning of the end for Assad. But observers point out that he still has many supporters, especially among minorities worried about sectarian bloodletting and residents of Damascus, Aleppo and other cities.

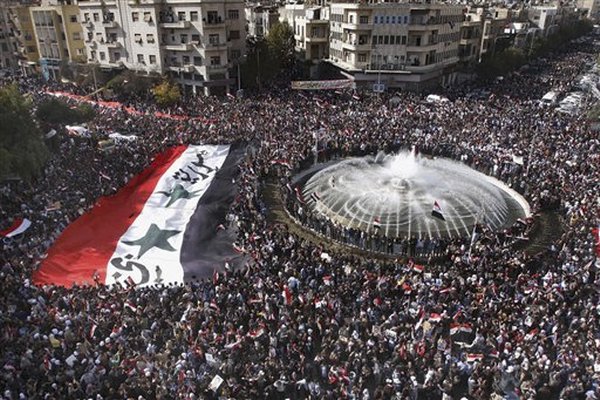

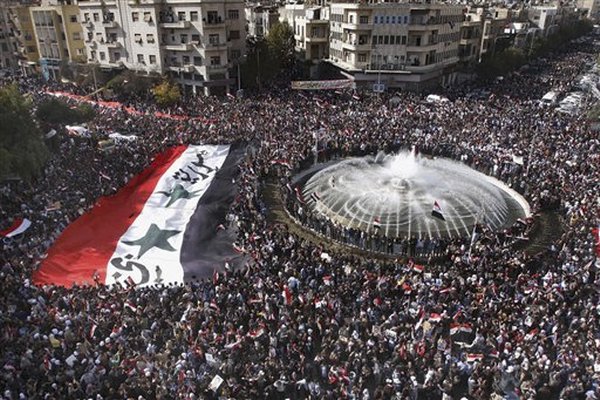

The state-run news agency reported Sunday that “millions of Syrians took to the streets” to denounce the Arab League’s action.

Meanwhile, opposition activists reported that at least 30 more people were killed Sunday in political violence, including 24 in the provinces of Homs and Hama. The reports could not be independently verified.

The United Nations blames a “brutal” government crackdown for the deaths of about 3,500 people, mostly civilians, since antigovernment protests began in mid-March. The Assad administration says militant Islamic “terrorists” have killed more than 1,000 security personnel.