By: Iftikhar Salahuddin

Source: Dawn

IT is Friday in Xi’an, the ancient city in Shaanxi province of China. The bazaar near the Drum Tower is preparing for the worshippers expected to attend the traditional Juma prayers at the historic mosque in the middle of the souk. The market is a city block of narrow, cobbled streets lined by shade-giving trees and quaint buildings that betray their Tang and Ming heritages. Shops for the tourists are aplenty, but the crowds mill around the eateries that offer varieties of freshly prepared local cuisine.

The prominence of sales girls in hijab and signs proclaiming the food halal leave no doubt that Muslim tradition is alive and well in this improbable outpost of Islam in central China. The food, however, is not for the faint-hearted: seahorses and scorpions on skewers are also on offer. Mercifully for us, the food in this bazaar is free of pork, which inevitably finds its way into almost every Chinese dish. Ordering a meal in sign language is a frustrating exercise but a local person, having noticed our predicament, helped us order a local delicacy, which we washed down with a yoghurt drink.

Fortunately, his Mandarin-accented English was quite intelligible; he was sporting a skull cap favoured by Muslims and seemed knowledgeable. We were curious about the origin of Muslims in China and asked him to join us for the meal, which then turned into a history session.

There are 20,000 Muslims in Xi’an, he tells us, and they own almost all the shops around the mosque. Ethnically they are Hui, from the northwest region. There are, in fact, over 10 million Hui people in China and most are Mandarin-speaking Muslims. The largest population of Muslims in China is in the northwest Xinjiang province. Ethnically, the Muslims there are mostly Uyghur. Recently, they have been under government scrutiny due to a surge of religious extremism in the region and violence by some unruly young Muslims. Our friend tells us that, contrary to recent rumours, the government’s attitude towards Muslims in China is fair.

There are 20,000 Muslims in Xi’an, he tells us, and they own almost all the shops around the mosque. Ethnically they are Hui, from the northwest region. There are, in fact, over 10 million Hui people in China and most are Mandarin-speaking Muslims. The largest population of Muslims in China is in the northwest Xinjiang province. Ethnically, the Muslims there are mostly Uyghur. Recently, they have been under government scrutiny due to a surge of religious extremism in the region and violence by some unruly young Muslims. Our friend tells us that, contrary to recent rumours, the government’s attitude towards Muslims in China is fair.

Xi’an served as the imperial city for 10 ancient dynasties; trade with Arab Muslims through the Silk Route originated here. It is, therefore, not surprising that very early in its history, during the Tang Dynasty in the seventh century, Muslim traders from Arab lands came over to China.

Among the first arrivals was Saad ibn Abi Waqqas, a close associate of Hazrat Usman. He brought a message from the caliph to Emperor Gaozong. The emperor received the Muslims well and honoured them by constructing China’s first mosque, the Huaisheng Mosque in Canton.

Later, many Muslims settled in Xi’an and eventually over the centuries prospered across China. They became particularly influential during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644); Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, the dynasty’s founder, had in his army six Muslim generals, including Lan Yu, who in 1388 led a strong army across the Great Wall to defeat the Mongols. In fact, Zheng He, the legendary admiral of the naval fleet of Ming Emperor Yongle (14th century) was a Hui born to a Muslim family.

It was during the Ming period that mosques mushroomed over China, and they all adopted the traditional architecture bequeathed by Tang and Ming period influences.

Our friend accompanied us to the ancient mosque, just around the corner from the restaurant. While there are many mosques across China, the Great Mosque of Xi’an dates all the way to the Tang Dynasty (circa 740) — about 100 years after the life of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). Over the centuries, additions and modifications were carried out, mostly during the Ming Dynasty and the Manchu (Qing) period. The mosque is enclosed in a brick wall aged by time and nature. It has a typical layout common to Chinese temples — one courtyard leading into the next, with pavilions and towers richly engraved with calligraphy and decorated with floral patterns. Each courtyard has rooms designated for various religious rituals and traditions. Surprisingly, contrary to Islamic injunctions against icons of living objects, sculpted dragons and birds adorn the scaffolds along its roof. Prominent in the open spaces are stone arches and towers etched with verses from the Quran.

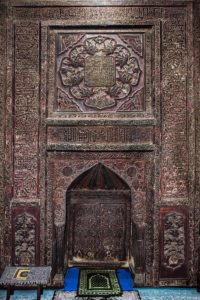

The last corridor leads to the prayer hall. Its entrance is framed with tablets engraved with floral motifs and calligraphy of verses from the Quran. The prayer hall is a large hypostyle leading to the mihrab, which is embellished with exquisitely carved arabesques and Chinese calligraphy in Arabic letters. While the hall is large enough to accommodate 1,000 people, our friend tells us that a typical congregation usually has around 100 worshippers.

The mosque is indeed an embodiment of the culture of ancient China. Muslims from around the world, familiar with the traditional minarets and domes of a typical mosque, are intrigued by the evolution of design from a classical Arabic to a quintessentially oriental façade. Indeed, devotion comes in many hues.

For more pictures of this fascinating locale see the original article at Dawn.

The writer is the author of Jerusalem — A Journey Back in Time.

Published in Dawn October 2nd, 2016.