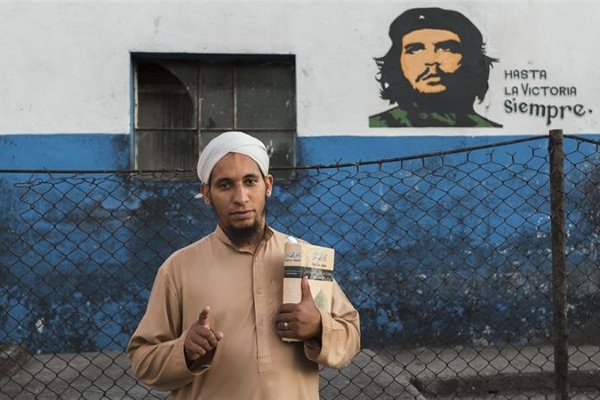

In Havana, Mohammed Dawud, 28, a Cuban convert, stands in front of a mural of Che Guevara [Carlo Bevilacqua/Parallelozero]

![In Havana, Mohammed Dawud, 28, a Cuban convert, stands in front of a mural of Che Guevara [Carlo Bevilacqua/Parallelozero]](https://muslimvillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Muslim-Cuba2.jpg)

Source: Al Jazeera

Santa Clara, Cuba – “Documents printed” reads a handwritten sign hanging outside the first floor of a house on the outskirts of Santa Clara, a university town in central Cuba.

Hassan Jan, 43, runs his makeshift printing shop from the front room of his home – part of a once-airy villa, now divided into four small dwellings, and surrounded by Soviet-style apartment blocks.

In the front room, which is separated from the rest of his house by a curtain, is a sofa, two chairs, a fish tank with goldfish and Hassan’s slow, noisy printer. Louvred windows do little to keep out the heat.

This kind of home-run micro-business has become common since Cuba relaxed its laws on self-employment in 2008.

A front room in a home will often double up as a telephone repair centre, barber shop or hair salon, whatever the neighbourhood needs. Hassan charges 1 Cuban peso ($.04) per sheet and rarely earns more than $1 a day. It’s just enough for him to support his wife Shabana and their two children.

Hassan, who has a dark beard and clear blue eyes, wears a dishdasha, the long white garment worn in many Muslim countries and a white head-covering. Beside an ornate 19th century clock on the wall above the computer hangs a photograph of Masjid al-Haram, the Sacred Mosque of Mecca.

Hassan and Shabana belong to a small but growing number of Cubans who have converted to Islam, or, as they put it, “accepted Islam”.

There are believed to be only a few thousand Muslims in Cuba, an officially secular, but largely Catholic country. The majority are foreign students or workers. Hajji Isa, formerly Jorge Elias Gil Viant, a Cuban convert and artist, and former librarian with the Arab-Cuba Union, a cultural organisation based in Havana, estimates that there are about 1,000 Cuban Muslims, both converts and descendants of Muslim immigrants.

“It’s a young community,” he says. “Muslims from abroad have been and still are a determining factor in the creation and development of the Cuban communities … Muslim students from African, Western Saharan, Yemen, Palestine and other Arab countries were a big influence in the 1990s, then later many from Pakistan.”

This, according to Isa, has meant that the small Muslim communities across the island have different characteristics, shaped by those who originally influenced them and local circumstances. As the number of Muslim converts grows, however, people are becoming more aware of Islam as a religion that’s also practised by Cubans. Small businesses, such as Hassan’s, help to bring more Cubans into contact with Muslims and also support the growth of the community.

“This has been a new field for Muslims and has helped them economically and to be able to support Muslim brothers,” Isa says.

Discovering Islam

Hassan’s path to Islam was an unexpected one.

Born Froilan Reyes, he had no religious leanings while growing up.

“I was brought up in the Cuban system,” he says. “I’d never even been in a church.”

A fun-loving party-goer, he worked as an audio technician at the University of Medical Sciences in Santa Clara and also did regular evening stints as a DJ.

This all changed in 2010 during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan when he was required to work with a group of Pakistani medical students studying at the university.

In 2005, an earthquake in Pakistan-administered Kashmir killed more than 86,000 people and left an estimated 2.5 million homeless.

Within a week, Cuba sent more than 2,000 doctors and other medical specialists to help the earthquake affected areas. The following year, it offered 1,000 scholarships for young people from across Pakistan.

Nearly 300 of them were placed at the university where Hassan was working.

Initially, Hassan avoided them.

“People spoke badly of the Muslims, called them terrorists, that sort of thing,” he says.

Then he was assigned to look after the audio requirements for the students’ prayers during Ramadan, and was with them from 2pm until 2am every day.

“At first I was very uncomfortable,” he admits. “I was angry with them because I was afraid. They would invite me to break fast with them, but I refused because I didn’t want to eat with them.” He smiles, shaking his head at the memory.

“I remember the third day. They were all praying and I said to myself, ‘What on earth am I doing here?’ I was completely out of my comfort zone. And so it went on until one day I agreed to eat with them and began to talk with them. I saw they had sacrificed a lot to continue with their faith in Cuba,” he says.

“I asked myself, ‘Well, if they’re so bad, how come they’re being so good with me?’ And so I began to talk with them more and realised Islam was something different to how the Cubans talked about it.”

Once Ramadan ended, he resumed his regular job, but continued to see the students and began to read the Quran and to discuss it with them.

Seven months later, he converted and changed his name.

“Allah showed me through the way they behaved that Islam was something else: Islam is peace, it’s the will of God. Allah gave me the opportunity to understand that. It was a gift for me,” he says with a broad smile.

Hassan’s decision to convert initially created problems with his extended family.

“My family at first were against it. Because, like I said, it has a bad reputation. That‘s all people know. And it was difficult. There are still people in my family who don‘t accept that I‘ve accepted Islam.”

His wife was also hesitant at first.

“I didn’t want to convert because of the things people said – that they abused the women. But I read, I read a lot, I looked for books so that I could understand better,” she says. She converted five months after her husband and changed her name to Shabana.

“At first I didn’t wear the hijab because of people, because I was afraid of what people would say. But then after a year, it entered my heart and now I wear it and even here in the house I forget that I have it on.”

Their children, Aina,16, and Ismael,12, also wear a headscarf and dishdasha.

“It’s quite hard for my daughter at her age,” Shabana says. “She’s 16 and it’s difficult for her at school. I just hope she meets a boyfriend, a man who is Muslim and who can help her. We’ll see. As God wills.”

Being Muslim in Cuba

Links between the cultures of the Middle East and Cuba go back centuries.

Moors from Andalusia were brought as slaves by Spanish conquerors, with records of this dating back as early as 1593. Over the following centuries, both Muslim and Christian traders from the Middle East were drawn to Cuba by the wealth the sugar trade was generating. Many stayed, mostly in Havana or around Santiago de Cuba, the second-largest city at the far east of the island. Most Arab immigrants, both Muslim and Christian, gave up their religion once in Cuba.

Cuban culture today invariably poses challenges for the country’s practising Muslims. Rum is one of the main items sold at cafes. It’s a popular drink, not least because it costs significantly less than a soft drink. Pork features heavily in Cuban diets – it is the meat of choice for every celebration. Supermarkets have recently started importing halal chicken from Brazil, which is unaffordable for most Cubans. Clothes, such as the dishdasha or head-covering, have to be brought into the country or are left behind as gifts by Muslims from other countries.

“Many brothers from other countries have said to me that we Cuban Muslims are the real Muslims, because it is so much harder to observe here than in a country where many people share the same beliefs and practices,” Isa says.

Hassan struggled in the beginning.

“Food is difficult because everything’s forbidden. The meat we eat most is pork, which is forbidden … And really there are a lot of temptations in the street. To be honest, it is a bit difficult, but Allah gives you the strength to go on,” he says.

Since converting to Islam, Hassan and Shabana’s lifestyle has changed completely, and is now centred on time spent at home.

“I‘m very happy in my house, I‘m quiet. I don‘t go out much,” Shabana says.

“I go out if I need to get something, or to go to the doctors, but not because I want to be in the street,” she says.

Perceptions about Islam

Cuba’s converts also face challenges stemming from the lack of understanding that many Cubans have about Islam.

Media reports about terrorist attacks and conflict in the Middle East have shaped many Cubans’ perception of the religion.

This is something Hajji Jamal is keen to change.

He makes his living as a taxi driver in Santiago. Like many Cuban converts, he was raised Christian.

“I was a member of the Baptist church. I knew a lot about Christianity, but I could never really understand the Holy Trinity. Then I met a Cuban Muslim who’d been Muslim for many years, and started to talk with him about Islam. He gave me a Quran and said, ‘Read this’. It took me a while, but then eventually I did read it and I could see a logic there, it seemed very sincere, very real and it was this which attracted me to Islam.”

Jamal converted in 2009.

His mother, however, was appalled with his decision. Initially, she wanted him to leave the family home, but relented soon afterwards, allowing him to stay so long as none of his Muslim friends came into the house. When she saw Jamal and his friends standing outside in the sun she softened a little. She now invites them in for a meal.

“She still doesn’t accept Islam, but the Muslims she knows yes, she welcomes them, prepares them food, everything,” he says.

Jamal is an informal representative of Santiago’s Muslim community of about 30 Cubans and 90 foreign students. He works with the authorities, whose presence is widespread with over 70 percent of the population working for the state, to increase their knowledge and understanding about Islam.

“We‘re trying to give the best possible example of Islam, for at the moment there‘s a lot of negative messages in the media. People generalise, thinking, ‘If you‘re Muslim, you must be a terrorist‘.”

He says: “Many are perverting the image of Islam. Islam is peace. So that is the message we are taking. Not because we expect people to convert, but so they can live comfortably together with Muslims.”

Jamal says freedom of religion is respected under Cuban law.

“[Problems come] usually from authorities in small places who are interpreting the law in their own way. Because the law itself is clear – people can’t be discriminated against by race, religion or colour,” he says.

Some of the Cuban women converts who wear a headscarf have faced objections and discrimination from the authorities in their workplace or universities. According to Isa, such situations are usually resolved through discussion and explanations of what Islam is about. Shabana, however, says that for her “it got complicated” and she left her job. She now provides childcare at home for the son of a Muslim student.

She is reticent to talk about what happened at her former job. “It was just ignorance,” is all she wants to say.

Shabana, like a number of Cuban converts, feels there’s an active role for Muslims to play in increasing understanding among other Cubans about what Islam is.

“When I go out it’s also good, people always ask about the headscarf and in answering their questions they learn something about Islam and that way people begin to adapt. So that they know what Islam is, that it isn’t what people say,” she says.

Sport Café: Vegetarian pizzas and conversations about religion

Small businesses serving local communities play a role in generating conversations about Islam in Cuba.

Jorge Miguel Garcia, whose Muslim name is Khaled, is a part owner of a café in Santiago which is both an informal meeting place for the Muslim community and popular with non-Muslim Cubans.

Khaled converted to Islam from Baptism, and his wife of 20 years remains a Baptist.

He used to work in forensic medicine, but when the government enabled Cubans to start setting up small businesses he jumped at the opportunity.

His initial idea was to import motorcycle parts, but with importing businesses not currently on the list of enterprises allowed in Cuba, he instead set up Sport Café with a non-Muslim friend.

They sell dishes which include pork, but Khaled hopes one day to run the cafe completely in accordance with Islamic precepts. He believes it can still be a viable business.

“It’s true that Cubans are very attached to pork products,” he says, “but things are changing and people are more willing to try new dishes. Already I sell vegetarian pizzas, which you don’t see elsewhere, and unlike other cafes, we don’t serve alcohol and that’s never been a problem.”

For him, the café is a valuable, albeit unintentional, way of increasing Cubans’ understanding of Islam.

“People who come for the first time always ask me about Islam and I like that, that they are interested. Many come back specifically because they see it as a healthy place where everyone is treated with respect. Those are the principles of Islam: peace, love and submission to Allah.”

A community in the making

In 2015, a museum in Calle Oficios in Old Havana was turned into a prayer house with the support of the Office of the Historian, the body responsible for the restoration of central Havana.

It is the closest thing to a mosque that Cuba currently has and is where Muslims in Havana can go for Friday prayers.

In other towns, the solutions are informal, with people setting up prayer rooms in their own homes.

Hassan and Shabana have a small, rug-filled space in their house where other Santa Clara Muslims come to pray.

“We don’t have much to offer them,” Shabana says, “but brothers and sisters are always welcome.”

Jamal says a community prayer space for Muslims in Santiago is a priority.

As yet there is no approval, or funding, for a mosque.

“We’re building a small space, about 12 square metres, to pray in. Hopefully in the future – God willing – they’ll let us build a proper mosque. That way we’ll be able to interact as a community, learn from each other – it’s always good to meet and learn from people in other countries.”

Some support comes from outside. Saudi Arabia has funded language labs in both Havana and Santiago and in 2014 had a stand at the Havana Book Fair where literature about Islam and copies of the Quran in Spanish were distributed. King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, who died in January last year, sponsored five Cubans to make the Hajj pilgrimage in 2014. It’s a near-impossible dream for most Cuban Muslims, with state employees earning around $20 a month.

Jamal and Isa were fortunate to be among the five.

“I never expected to go on Hajj so early,” Jamal says.

“When I arrived at Jeddah, at the airport, the first thing I heard was the sound of prayer, and I began to cry,” he recalls.

“Cuba has changed for sure,” Jamal says. “But for me things will really have changed when we’re allowed to build our own mosque, our own centre of studies – to have the same privileges that other religions have. When women can wear the veil without any problems. Those will be the real changes.”

This story is part of the My Cuba series. More stories from the series can be read here.