By: Akbar Ahmed

Source: The World Post

“The loss of Andalusia is like losing part of my body,” H.R.H. Prince Turki al-Faisal told me.

I had asked him what the loss of Andalusia meant to him as an Arab. The son of King Faisal, widely celebrated in the Muslim world, Prince Turki heads The King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia’s preeminent think tank, and has been Saudi ambassador to the U.S. and the U.K. The question had excited the normally taciturn prince. The mask of cultural and royal impassivity developed over a lifetime of diplomatic dealings had dropped as his body and voice expressed high emotion. The image of Andalusia had struck a nerve: “The emptiness remains.”

“‘Andalusia was the exact opposite of Europe at that time — [then] a dark, savage land of bigotry and hatred.'”

When I asked him what Andalusia meant to him, he replied, “I have a passion for Andalusia because it contributed not only to Muslims but to humanity and human understanding. It contributed to the well-being of society, to its social harmony. This is missing nowadays.” For the prince, “Andalusia was the exact opposite of Europe at that time — [then] a dark, savage land of bigotry and hatred.”

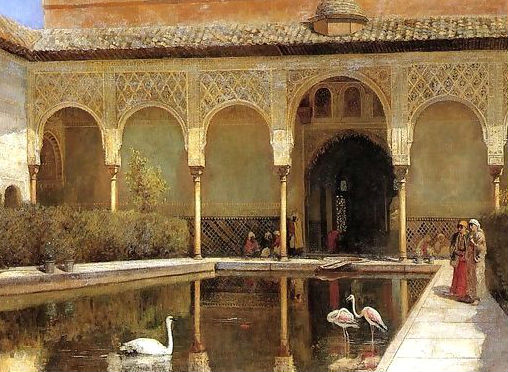

At its height, Andalusia produced a magnificent Muslim civilization — religious tolerance, poetry, music, learned scientists and scholars like Averroës, great libraries (the main library at Cordoba alone had 400,000 books), public baths, and splendid architecture (like the palace complex at the Alhambra and the Grand Mosque of Cordoba). These great achievements were the result of collaboration between Muslims, Christians and Jews — indeed the work of the great Jewish Rabbi Maimonides was written in the Arabic language. It was a time when a Muslim ruler had a Jewish chief minister and a Catholic archbishop as his foreign minister. The Spanish had a phrase for that period of history — La Convivencia, or co-existence.

The civilization of Muslim Spain was the embodiment of the Islamic compulsion to seek ilm, or knowledge. Andalusia produced many firsts, the first person to fly, Ibn Firnas, after whom a moon crater was named in present-day Cordoba, as well as a bridge in present-day Cordoba and the first philosophical novel, by Ibn Tufail. Through Spain, Europe received models for universities (Oxford and Cambridge are examples), philosophy and literature (for example the work of Thomas Aquinas), and the study of medicine originating from the work of Avicenna and Abulcasis.

Prince Turki connected Andalusia with the earliest days of Islam and talked excitedly about the charter of Madina, which he said was the first written constitution for society providing a social framework for the state itself. He underlined the importance of the concept of knowledge or ilm in this vision. Ilm, he pointed out, meant studying the Quran, fiqh, or Islamic law and hadith, or the sayings of the Prophet. But ilm also included the learning of non-religious subjects such as mathematics and science. “Andalusia,” the prince sighed, “transcends space and time.”

He described the lure of Andalusia in his desire to pray in the mehrab of the Grand Mosque of Cordoba. As the Spanish authorities very consciously claim the building to be a cathedral, Muslim prayers are specifically banned. Yet the mehrab has attracted Muslim visitors like moths to a flame. It was here that Allama Iqbal visiting from British India could not resist sitting down to pray. His image at prayer in the Grand Mosque is known throughout the Muslim world. Iqbal’s famous Urdu poem, “Mosque of Cordoba,” which hangs in the office of the mayor of Cordoba, was written after his visit.

Following Iqbal and that iconic image, I prayed on the same spot in the early 1960s when I visited Cordoba as an undergraduate. The security guards were few in number and disinterested in the visitors. They merely looked away. The scale of both the Muslim achievements and the Muslim loss weighed heavily on me even then as a young man not quite 21 years in age. Andalusia made me feel that there was a special part of my history in Europe that was not known and yet I found it so compelling. The prince recounted saying his prayers on that very spot at the mehrab, too, during his visit in the 1980s when the authorities gave him special permission. “You cannot help yourself,” he said softly, as if to himself.

“‘Andalusia,'” the prince sighed, “‘transcends space and time.'”

Security was much more strict in the 1990s when I was filming “Living Islam” for BBC TV, and I noted that there was a thick silken rope which acted as a partition to block off entrance into the mehrab. Our English producers, however, managed to convince the guards with that mixture of bravado and arrogance they reserve for the continent. I was thus able to pray in the mehrab, which was recorded by the BBC for the section on Andalusia. Our attempts to pray there failed miserably in the summer of 2014 when we were there to conduct a study of Islam in Europe. Not only had the authorities built high ugly steel railings to prevent anyone coming close to the mehrab, the security guards and church officials hovered around inside the mosque. They were on high alert as rumors of Muslims determined to reclaim the mosque for Islam were circulating. Every time we came near the mehrab, the guards would close in and ask us to move along.

Dr. Amineh Hoti, a member of the research team, made it a habit of visiting the mosque, just opposite our hotel, when it opened first thing in the morning — and then again during the day. She appeared to be in a trance, and I saw that Andalusia was already working its magic on her. As a father, I nonetheless worried that she may try to say her prayers and get in trouble with the security people. Thankfully there was no untoward incident.

Around that time, Amineh interviewed a educated young, married woman with a Syrian background and asked her what the loss of Andalusia meant to her. The Arab woman could not control her emotions. She burst into tears. Amineh, who was already pent up, also began to cry, and as the two put their arms around each other and sobbed, the guests in the lobby wondered about the source of the bereavement. Later, Amineh was able to excitedly point to Iqbal’s famous poem hanging just behind the mayor in his office when we called on him. She introduced the topic of Andalusia to her students in Lahore and was able to help them think about how to live with those of other religions and cultures.

The question of why and how it all ended for Muslims still remained. When I asked the prince the eternal questions — What went wrong? Why did Islam collapse so soon after the fall of Andalusia? — he blamed it on the loss of Andalusia itself and then the sustained assaults by the Crusaders from the West and the Mongol eruptions from the East.

“Europe destroyed Andalusia,” the prince explained. “With the loss of the spirit of Andalusia was lost the idea of service to humanity. The circle of European ignorance and bigotry was now complete.” But Muslims and Jews who would be eventually expelled from the Iberian Peninsula were not the only victims. “Nobody was spared,” he said. “Christians themselves now faced the horrors of the Inquisition.”

Spanish rulers were obsessed with erasing Muslim history or replacing it. Charles V was shocked to see the travesty that was the doing of his officials in converting the Grand Mosque in Cordoba to a cathedral. He uttered his immortal words to the effect that they had taken something unique in the world and made it a commonplace available everywhere. Charles would himself attempt a similar exercise at the Alhambra in a palace that still stands inside the historic site. Thankfully the damage to the Alhambra remained minimal as it was not seen as a religious building.

History became an exercise in self-deception. For example “El-Cid,” and the prince smiled when he mentioned the film about the Spanish hero starring Charlton Heston, was nothing more than a “mercenary.” “He fought for money,” he said.

Around the time when Muslims were facing defeat in Spain, the Mongols erupted from the East to attack the heart of the Muslim world. He talked of the destruction of the libraries and books in Baghdad when that city was captured in 1258. “Centuries of civilization was razed to the ground.”

“Andalusia at its height shows us clearly that associating a group like ISIS with Islam and calling its leader a caliph is a travesty.”

History seemed to have stopped for the Arabs after the destruction of Baghdad in the 13th century. There would be great Muslim empires in the future — the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals — but they would not be Arab. They would be Turk, Persian and Indian. In contrast, Andalusia was a civilization brought to Europe primarily by the Arabs. Arabic was its lingua franca and Islam its dominant religion. The founder of the greatest of the dynasties of Cordoba was Abdur-Rehman, known as the “falcon of the Quraysh,” a prince with kinship ties to the prophet of Islam himself.

Once the destruction began in the West and the East, it could not be stopped. It spread like the apocalypse. Mosques, libraries and baths — anything that reminded people of Islam — were systematically destroyed in Andalusia. It was the same in the East. The Mongols did not stop at the destruction of Baghdad. Prince Turki especially regretted the destruction of Samara, a city patterned on the legendary Madinat al-Zahra in Andalusia. Visitors from Spain would describe the marvels of that city to the court in Baghdad and the caliph was determined to create a similar city outside Baghdad. Now, like the original, it lay in ruins. The irony was that while Mongols destroyed Muslim cities in the East, the Andalusian Madinat al-Zahra was reduced to rubble by Muslim tribes from North Africa, which overthrew the dynasty in Cordoba and were expressing their contempt for the Andalusian way of life.

There were two distinct Muslim responses which emerged from that time and would cast their shadows on the present. Both Jalaluddin Rumi and Ibn Taymiyyah lived at the time of the destruction of the Arab world. Rumi was alive when Baghdad was sacked. Ibn Taymiyyah was born five years after its destruction. The impact of that time is clear in the way these two looked at the world. Rumi responded by consciously rejecting barriers and differences between people and reaching out to everyone with love. Ibn Taymiyyah responded in exactly the opposite way by underlining the threat to Islam and advocating for the drawing of rigid boundaries around the faith. He famously issued a fatwa against the Mongol rulers, even those who claimed to have converted to Islam because they did not adhere strictly to the sharia. He declared a jihad against them which was compulsory for all Muslims. The notion of Islam in danger may be traced to Ibn Taymiyyah. Both men continue to influence Muslim thinking in our time. Mystics throughout the world are inspired by Rumi, groups like the Wahhabis and the Salafis draw their inspiration from Ibn Taymiyyah.

How did the prince see the condition of the Muslim world today, I asked. Is it as simple a division as suggested by the binary between Rumi and Ibn Taymiyyah? The prince in reply stretched out his hands to indicate that the ideological movements today are like so many fingers flowing in parallel but different lines.

Prince Turki’s passion for Andalusia is neither idiosyncratic nor restricted to his generation. He told me the story of his famous father visiting Spain as a guest of General Franco. When Franco asked him how he could accommodate his royal guest, King Faisal said he would pay for the construction for the most magnificent cathedral in Europe if the general could give him the Grand Mosque of Cordoba. Franco said the building meant nothing to him and he had no objection. He could hand it over the next morning. But if he did so, he would be lynched by the people of Spain. As an alternative he offered the king the best piece of land in Madrid itself, atop a hill overlooking the city. King Faisal accepted the land and built what is now the Islamic Center there.

“‘You don’t have a monopoly on what is right.'”

I was able to interview the prince at the Ditchley Conference on Islam in March 2015. We spent several days together at the historic estate — famous as the country retreat of Churchill during the Second World War and located next to his ancestral home, Blenheim Palace. I requested the prince for a one-on-one interview in the context of my study of Islam in Europe. He was enthusiastic about the project and invited me to his center to present the findings when completed. During the interview he was relaxed, thoughtful and courteous. We both understood that the answer to my final question was in fact a matter of immediate concern to Muslims and non-Muslims everywhere. What lessons could Muslims and non-Muslims learn from Andalusia?

“To be more humble, he said. “Not to think that they have all the answers.”

The prince urged both Muslims and non-Muslims “to be inclusive. You don’t have a monopoly on what is right.” He emphasized the idea of ilm, the need “to continue learning till we die,” never to abandon “the search for knowledge.” The lesson of Andalusia, above all, appears to be that history does have lessons to teach us. Andalusia was about a common “humanity.”

Spain has much to teach people about how those of different religions and cultures can live together in harmony and thrive. It can remind us of the Spanish concept of La Convivencia. Both Muslims and non-Muslims will benefit from being reminded of Andalusia. They will also know that Andalusia at its height shows us clearly that associating a group like ISIS with Islam and calling its leader a “caliph” is a travesty. And there is no lesson greater for everyone than to recall that there was a time, however brief, when people of different cultures and faiths lived together, worked together and prospered together.