By: Dr Cemil Aydin

Source: http://www.thenational.ae/

As we prepare to mark the centennial of the outbreak of the First World War this summer, many still see it as primarily an inter-imperial struggles within the European continent, with the scenes of trench warfare on the Western Front.

It is often forgotten that this war was as much about the political destiny of what was then and now called “the Muslim world” as it was about Europe, with Muslim soldiers fighting on both sides of the imperial alliances.The declaration of jihad by the Ottoman caliph, the revolt of Sherif Hussein of Mecca and the eventual end of Ottoman rule in Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem marked the important turning points, followed eventually by the abolishment of the caliphate during the post-war restructuring of Turkey.

Moreover, the persistence of a debate on a pan-Islamic “threat” to the West and Islamophobia seems one of the surprising continuous themes from the time of the First World War to today, after a passage of a century during which the world of empires gave way to a world of nation states.

There are important lessons to be learned from the Muslim question of that time for both Muslim leaders of today as well as for United States and European politicians.

What ties our contemporary world to the climate of opinion at the time of that war is the continuing debate on the question of “the Muslim world” and “the West”, two imagined civilisational and geopolitical entities.

When the US president, Barack Obama, made his Cairo address “to the Muslim world” in 2009, he was confirming this modern assumption that there is a global Muslim community that has to be engaged politically and intellectually. There are many Muslim intellectuals, politicians and activists who also share this vision of “the Muslim world”, and often refer to the religious notion of Ummah and the need for its solidarity.

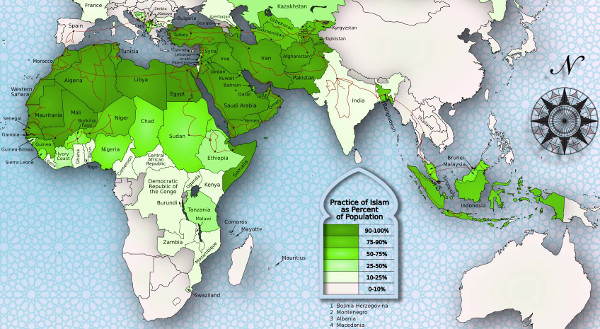

It is almost unthinkable for a world leader to appeal to “the Christian world” or “the Buddhist world” in a similar fashion. Why does the term “the Muslim world” have such a well-entrenched academic and political credibility, despite the obvious naivete of categorizing one and a half billion people, with a striking range of diversity on every topic, into one imagined geopolitical unity? Given the widespread overutilisation of the term “the Muslim world”, in the last century, it is essential to ask when this term originated and how it has been employed in modern history.

Whatever the nature of contemporary discourses on Muslim solidarity, it would be mistaken to assume that Muslims were united throughout history, and they only became divided due to European colonialism or nationalism. On the contrary, it was at the peak of European colonial hegemony in the early 20th century that we saw the emergence of a global Muslim identity and public opinion.

Throughout the millennium from the 9th to the 19th centuries, Muslim societies were ruled by multiple kingdoms, sultanates and empires, many of which were in conflict with each other. There has always been a cultural commonwealth of Muslim societies facilitated by the network of educational institutions, legal practices, Sufi orders, religious rituals such as pilgrimage to Mecca, and trade, but never a political unity, which was logistically impossible given the geographical scope of the spread of Islam.

Despite the reputation of colonial policies of “divide and rule,” late 19th century western imperial globalisation over Asia and Africa counter intuitively united Muslims, by fostering more intense trans-Muslim networks of education, communication, publishing, transportation, trade and pilgrimage.

During the opening ceremony of the Suez Canal in 1869, Khedive Ismail famously said that Egypt would be part of Europe thanks to this world historical event. Yet, within 40 years, the Suez Canal became instrumental in making Egypt a part of Asia and the Muslim world, not necessarily a part of Europe.

British-made steamships carried more Muslims to pilgrimage sites in Arabia and allowed more Muslims to travel and connect with other Muslims. At the same time, printing technologies and telegraph and postal services were carrying Muslim publications to different parts of Asia and Africa. The Suez Canal linked Egypt not only to Europe but also to India, Africa and East Asia, meaning Arabic-language journals of Cairo, such as Al Manar found subscribers in such faraway places as Singapore, Bombay and Kazan.

A vibrant Muslim press, travel and trade created an informal pan-Islamic commonwealth of identity, political sympathies and emotions, overlapping, utilising and challenging the formal empires of Europe that ruled over them.

Thus, a century ago, on the eve of the First World War, many Muslims (as well as colonial officers of various European empires) believed in the existence of a geopolitical unity called the Muslim world. Some of these transnational Muslim activists imagined the leadership of the Ottoman Caliphate in the emerging public sphere of a Muslim world divided into multiple European empires, but what mattered most was the vibrancy and mobility through the existing Muslim networks. Ironically, the empire that had the largest Muslim population in the world was the British Empire, not the Ottoman Empire. Some Muslims called it “the greatest Muhammedan power in the world”.

Today, a century after the trials and tribulations of the British Empire, a post-Cold War era US superpower has to deal with a similar set of puzzles, dilemmas and contradictions with regard to its policy towards an imagined Muslim world, now divided into more than 50 nation states compared to living under the rule of five major empires a century earlier.

At the same time, due to America’s political entanglements with Iran, Palestine, Afghanistan and elsewhere, its elites also perceive a growing and more assertive Muslim public opinion as a threat to its interests, which became confirmed in the US imagination in the September 11 attacks by Al Qaeda.

In return, US and European Islamophobia helps foster a stronger sense of global Muslim identity. There may not be much connection between Indonesian, Uzbek and Nigerian Muslims, but if they are all subjected to similar discourses of Islamophobia, they may express shared sentiments towards, for example, the publication of Danish cartoons, or the burning of a copy of The Quran by a fundamentalist American pastor, which will then raise a renewed wave of suspicion about global Muslim solidarity.

Political Islam uses the argument that the Muslim Ummah is being humiliated and is in crisis, and thus needs pan-Islamic solidarity. Yet, an imposition of a particular pan-Islamic ideological vision itself aggravates the natural diversity of ethnicity, language, class, gender and ideological orientations among world Muslim populations.

This historical overview of the modern trajectory of the idea of the Muslim world should not mean to imply that contemporary Muslims do not have any right to imagine a humanitarian or political solidarity of Ummah. Muslims of different kinds have all the rights to show concern about the conditions and destiny of their co-religionists or other human beings, talk back against discrimination and racism, and they have a right to act on their internationalist and humanitarian visions.

Here, a scholar of international and intellectual history can only suggest that both Muslims and non-Muslims alike pay attention to the recent history of the utilisation of the idea of Muslim unity or Islamic threat, and do not make ahistorical and essentialist assumptions about the experience of being Muslim in the modern world. This historicisation can help us overcome not only the obsolete binaries of “the Muslim world” and “the West”, but also reveal the entangled essentialisms of Islamophobia and pan-Islamic revivalism.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of MuslimVillage.com.