By: Laura Overmeyer

Source: Qantara

Melih Kesmen designs Islamic fashion, which has brought him a great deal of international success. Laura Overmeyer relates how Kesmen, a German Muslim, developed his spontaneous idea into a successful concept and how fashion can be used to promote interreligious dialogue.

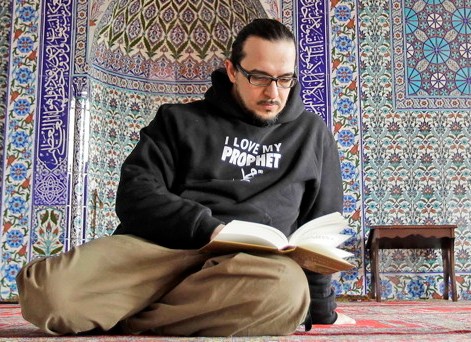

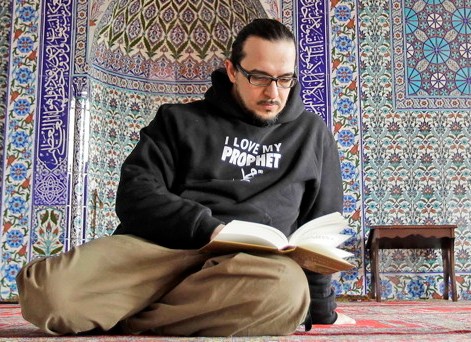

“I love my Prophet”

“I love my Prophet”. In the autumn of 2005, Melih Kesmen walked through London with these four words on his chest, never suspecting how this would change his life. He had the words printed on a T-shirt in response to the on-going discrimination against Muslims in Europe, a situation that the young Kesmen had personally experienced.

As was the case for many, 11 September 2001 was a turning point in Kesmen’s life. And as chance would have it, he found himself on his honeymoon at the time. When he and his wife returned home to Germany, the country had noticeably changed.

Suddenly, the young Muslim pair faced an unaccustomed degree of alienation and insecurity. This development was only further intensified by the invasion of Iraq two years later and the subsequent terror attacks on Madrid and London.

Both in his native Germany as well as in London, where he began working in 2003, Kesmen felt increasingly ill at ease, almost to the point of powerlessness. “I had the impression the whole time that I had to bear responsibility for things I didn’t even know about and for views opposed to my own. It was incredibly stressful!”

Message with a surprise effect

Confronting stereotypes against Islam head-on: “I had the impression the whole time that I had to bear responsibility for things I didn’t even know about and for views opposed to my own,” says Melih Kesmen, founder of the Styleislam labelThe straw that finally broke the camel’s back was the furore over the Mohamed caricatures in autumn 2005. Kesmen was simply tired of having to justify himself and was fed up with the strange looks he was getting. He wanted to send a message – one that could be emblazoned on his chest. He had a T-shirt printed with his avowal of love for the Prophet and then wore it around London.

He was suddenly approached by people asking about the T-shirt, its meaning, and its message. Whether in the middle of the street, in cafes, or on the subway, he became engaged in constructive dialogues on an equal footing with his interlocutors. Many of his fellow believers were also enthusiastic about the idea of wearing such a T-shirt.

“It became clear to me that I wasn’t the only Muslim wanting to convey a message to society in a non-verbal way with a statement on my chest – a statement that is positive and speaks for itself. This revelation opened up a thousand doors in my head.” The idea of Styleislam was born.

Eight years later, it seems as if Kesmen still finds it hard to believe how far his original idea has developed. “The fashion label Styleislam offers you modern streetwear clothing with a casual cut and an extra portion of religion,” is how the label describes itself on its Internet shop site.

In 2008, Styleislam went on-line and has since enjoyed increasing popularity, and not only in Germany. The first stores have already opened and the number of staff is continuously growing. There have even been collaboration efforts with outside designers, often non-Muslims, who have been attracted to the unusual project.

In terms of fashion, the outstanding feature is less the cut of the clothes – although there have been creative new developments in terms of women Muslim fashion here – than the slogans and design.

Besides “I love my Prophet”, there is now a whole range of additional messages, which can be individually printed on T-shirts, pullovers, and various accessories. Some of these are specifically Muslim messages, such as “Salah keeps together” (Salah is the practice of formal worship in Islam), “Ummah. Be part of it,” and “Hijab. My right, my choice, my life”. There are also messages for non-Muslim customers, for example “Terrorism has no religion” and “Make Çay, not War,” which allow them to display their tolerance and pacifist beliefs.

“Pop-Islam” and interreligious dialogue

The majority of customers are, nevertheless, Muslim, mostly young and educated. In addition to the clothing style, a main reason for the label’s popularity is that young people and teenagers, in particular, often grapple with their religion and identity. Kesmen sees both concepts as being intricately entwined.

According to Kesmen, especially young Muslims in countries such as Germany face difficulties, as there is a popular belief that Islam and Western values are incompatible. Opposed to this is what experts refer to as the “Pop-Islam” movement, its adherents being mostly young Muslims. Its aim is to not only show that the combination of conservative religious practices with a modern lifestyle is possible, but that it can even be a defining factor for one’s identity.

Kesmen also fits into this trend. He hopes to help young Muslims in their search for an identity through his fashion label. He says he is acting in the interests of society.

A further goal of his work is to promote interreligious dialogue in society. “Of course, I know that I won’t be able to achieve miracles. Styleislam is only a Muslim streetwear label. But if our products move people to think more about these issues, encourage constructive dialogue, or even prompt them to read a book, then I have already done more than I ever imagined I could do.”

Success beyond all borders

A real surprise for Kesmen was the enthusiastic response to his label from abroad, particularly from the Arab world. “I naively believed that Styleislam was an exclusively European Muslim project, because it reflected the thinking of Muslim youth in Europe. Yet, I realized that even in an arch-conservative country like Saudi Arabia, people are receptive to the same message, although they perceive it in a totally different way.”

While Muslims in Europe feel encouraged to adhere to their religion despite a modern lifestyle, young people in Saudi Arabia are attracted to the label as a form of protest against their country’s dogmatic religious elite. Rebellious youth want to demonstratively show to their elders that they won’t let their lives be dictated to them.

In Saudi Arabia, the label has since opened up three stores. The Saudi authorities are said to be anything but overjoyed at this development. There are constant disputes with custom officials, who resist letting such “heretical” goods into their country. Yet, to date, not a single stone has been thrown at their store window displays.

Interest in fashion is also great in the neighbouring Muslim countries. Turkey can already boast two stores, while there are plans to soon open the chain in Egypt and Tunisia as well.

Without a doubt, Kesmen has found a market niche with Styleislam. Or, as he puts it, it is “a market that we form and construct, although no one knows the direction it will take. Everything seems possible.”