THE Malaysian medical fraternity has shown a timely initiative in holding on Oct 29 the first National Stem Cell Congress, opened by Health Minister Datuk Seri Liow Tiong Lai.

As the minister highlighted, “stem cells are arguably the hottest area of research” in many parts of the world, particularly for their potential to provide regenerative cures for heart, kidney and spinal cord diseases. This is potentially the “glorious light at the end of the tunnel” for hopeful patients suffering debilitating diseases.

Malaysia takes into consideration the ethical views and rulings of Islam on such research.

Islam through its ethical world-view is relatively open to many forms of stem cell applications compared with some other religious opinions.

The minister emphasised however, that, “If you cannot defend a study ethically, you should not and will not be allowed to conduct it.”

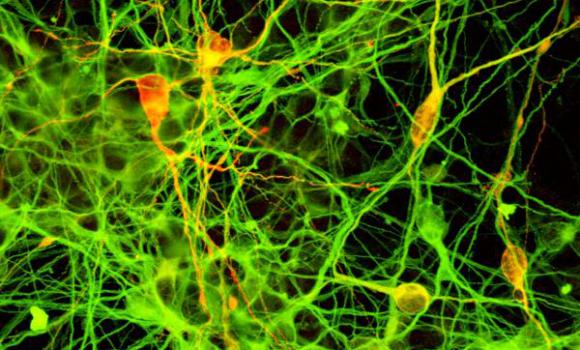

The unique properties of stem cells are that they are unspecialised and have the potential to divide and renew themselves and to turn into many different types of specialised cells for use in healing applications.

Islam is all for using science for the benefit of mankind, which satisfies a key objective of Islamic law — the public welfare. Specific syariah objectives for consideration in stem cell research include ensuring the protection of life, progeny and property.

Stem cell research and therapies using such cells are based on the utilisation of undifferentiated adult cells or embryonic cells.

Embryonic cells are generally preferred because they have the potential to develop into any type of human cell whereas adult cells are generally tissue-specific.

Last month’s Japanese Nobel prize winner, Prof Shinya Yamanaka, however, successfully programmed an adult cell into a stem cell, thus suggesting that embryos may not always be essential for stem cell research or therapy.

With precautions taken for the welfare of the donor, Islam condones the use of adult stem cells, which can be derived for example from bone marrow.

Use of embryonic cells though is more controversial. These are derived from aborted foetuses, excess embryos generated during laboratory in vitro fertilisation (IVF) when helping couples having difficulties conceiving a baby, or through cloning. It is argued that a benefit for research can be achieved in using surplus IVF embryos, which would otherwise be discarded.

The key ethical question with embryos and foetuses are at what stage after conception do they become a human being or a potential human, since Islam is firm against the taking of a life except in limited circumstances.

The applicable Quranic verses and statements of Prophet Muhammad in the 6th century C.E. were far advanced in providing knowledge on this scientific discipline, as pointed out by Canadian Professor Keith Moore in his textbook on embryology.

The prophet had said that “verily the creation of each one of you is brought together in his mother’s belly for 40 days in the form of seed, then he is a clot of blood for a like period, then a morsel of flesh for a like period, then there is sent to him the angel who blows the breath of life into him”.

This is taken by many scholars to indicate that the embryo’s status as a “human being” only begins four months after conception. Young embryos, they argue, could thereby ethically be used for research and therapies for human benefit.

Some scholars take the contrary view that an embryo is a potential human and should not be sacrificed even though a medical benefit can be achieved. Clearly, there are some challenging issues.

The Malaysian government in 2009 published its “Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Therapy”, which permit research on “human adult stem cells”, “stem cells derived from foetal tissues from legally performed termination of pregnancy” and “embryonic stem cell lines”.

This is the current position which could possibly change in the light of further research in bioethics and review of Islamic legal and ethical considerations. These are however, not yet well enough developed and are still awaiting new research and ijtihad by qualified scholars.

Much of the Islamic law-related discourse available on this subject offers general guidelines but grey areas persist. Such areas are the interface with the notion of “life” or “potential life” of the embryo, and whether an embryo can be destroyed in order to extract stem cells for medical uses.

Undoubtedly, the Health Ministry’s oversight committee, the National Sub-Committee for Ethics in Stem Cell Research and Therapy, will be kept busy with matters arising from the rapid growth in stem cell applications.

In deriving a legal decision (fatwa) in this field, Islamic hadith-cum-legal maxims are particularly relevant. Some renowned examples are “harm may neither be inflicted nor reciprocated” and “harm should be eliminated to the extent possible”.

In this respect, scientific research suggests that human embryos less than 14 days old do not experience pain or “consciousness”.

According to another Islamic legal maxim “the lesser of two harms is to be tolerated” if that is the only way to prevent a greater harm. Such could be applied, for example, to justify use of stem cells where they are able to overcome illness and relieve pain.

Islamic Bioethics was the subject of the international conference held in Qatar in June. Speakers included Tariq Ramadan and Sheikh Ali Qaradaghi, secretary-general of the International Union for Muslim Scholars.

Tariq Ramadan, during discussions held in Malaysia in July at the International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies, encouraged the bringing together of “scholars of the text (Quran, hadith)” and “scholars of the context”.

This position is supported by Sheikh Qaradaghi’s comments that fatwas relevant to biomedical ethics are only issued by the Islamic scholars after consulting experts and doctors as they are the specialists in the realm of science and medicine.