NEW DELHI // A third of India’s 140 million Muslims say they are suffering and pessimistic about their future – the worst of three ratings in a survey of Indian life.

Dalia Mogahed, a director and senior analyst at the polling company, said responses were assigned to one of three categories.

“Thriving is the highest category,” she said. “This is a person who evaluates their life positively today and expects it to be positive in five years. Suffering is the lowest and represents someone who rates their current and future life poorly.”

The other category, struggling, lies somewhere between the two.

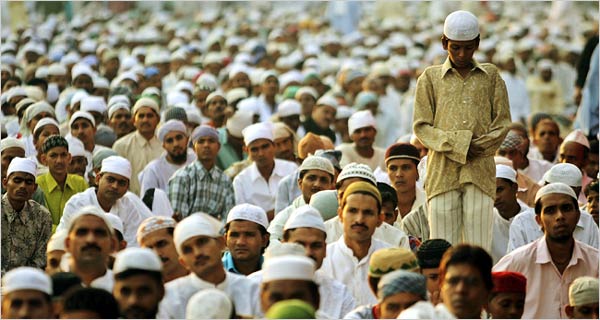

The survey revealed that 47 per cent of Indian Muslims said it was difficult to survive on their incomes, compared with 39 per cent of Hindus.

The poll showed that Muslims had larger families, with 29 per cent having three or more children, compared with 17 per cent of Hindus and only 7 per cent in other religious groups.

The poll did not give an explanation for the disparity between the economic situation of Indian Muslims and other groups. While it showed that Muslim Indians were “disproportionately more likely to be poor, uneducated and live in difficult conditions, it is difficult to say for sure what explains this discrepancy”, said Ms Mogahed.

More than 9,500 Indians, including 1,197 Muslims, were interviewed face-to-face last year and this year for the poll.

They were asked how they rated their lives now and the prospects for their future in five years, on a scale of one to 10.

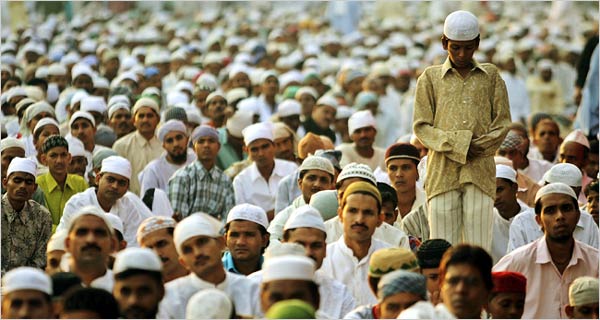

The Muslim population has increased 200 per cent in four decades, according to the 2001 census.

In comparison, the rest of the country’s population grew by 134 per cent. India has the world’s largest Muslim population after Indonesia and Pakistan.

The survey’s report cites a 2006 government study by the Sachar Commission, led by a former Delhi High Court chief justice, Rajindar Sachar, which examined the state of the Muslim community. The study related several anecdotal instances of discrimination.

“Muslim identity affects everyday living in a variety of ways that ranges from being unable to rent/buy a house to accessing good schools for their children,” read the commission’s report.

The authors said Muslims have only marginal access to credit and often work for wages less than their Hindu counterparts.

By comparing the number of Muslims employed in government offices, banks and universities to their proportion of the population, the report concluded that Muslims are under-represented in every area of the public and private sector.

Zikrur Rahman, the director of the India Arab Cultural Centre at Jamia Milia Islamia, believes the discrepancy is due less to open discrimination and a result of the lingering hangover from the country’s division in 1947, which resulted in the creation of Pakistan as a nation specifically for Muslims.

“We lost the upper-middle class,” Mr Rahman said. “These are people who would have been philanthropists, who would have run NGOs, or sponsored scholarships. They left a great void. Had there been no migration or partition, this would not have happened.”

The Sachar report also addressed the issue of education as “an area of grave concern for the Muslim community”. The commission found that Muslim children were more likely to have to drop out of school to help support their family.

Taimoor Khan, 22, left school at 17 to help his family survive. He works at a street food stall in Delhi’s predominantly Muslim Old City, after arriving in the capital five years ago from Uttar Pradesh.

After his father died, the family was forced to sell its food cart to pay off his debts. “We did not have the money to keep me in school,” said Mr Khan. “With no income, I was forced to find work.”

He supports his mother, two sisters and younger brother by sending home half his monthly salary of 5,500 rupees (Dh393).

Mr Khan doubts education would have improved his lot. “I don’t know what difference it would have made,” he said. He is not alone in thinking this way.

“Muslims do not see education as necessarily translating into formal employment,” said the Sachar report. “The low representation of Muslims in public or private sector employment and the perception of discrimination in securing salaried jobs make them attach less importance to formal ‘secular’ education.”