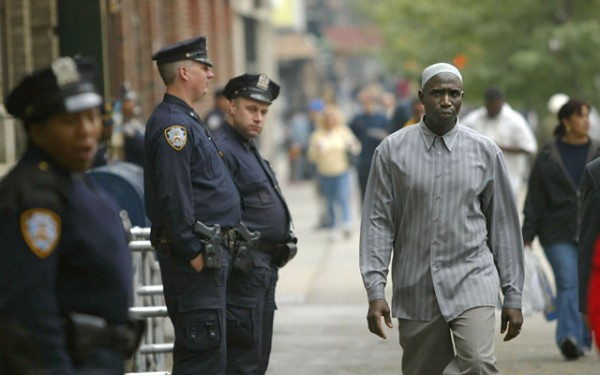

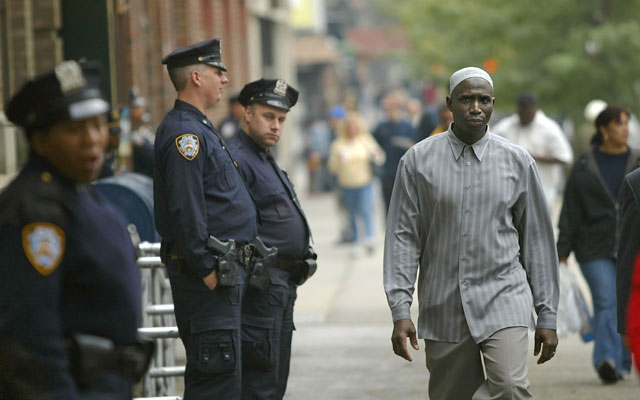

NEW YORK — Fed up with a decade of police spying on the innocuous details of the daily lives of Muslims, activists in New York are discouraging people from going directly to the police with their concerns about terrorism, a campaign that is certain to further strain relations between the two groups.

Muslim community leaders are openly teaching people how to identify police informants, encouraging them to always talk to a lawyer before speaking with the authorities and reminding people already working with law enforcement that they have the right to change their minds. Some members of the community have planned a demonstration for next week.

Some government officials point to this type of outreach as proof that Muslims aren’t cooperating in the fight against terrorism, justifying the aggressive spy tactics, while many in the Muslim community view it as a way to protect themselves from getting snared in a secret police effort to catch terrorists.

As a result, one of America’s largest Muslim communities — in a city that’s been attacked twice and targeted more than a dozen times — is caught in a downward spiral of distrust with the nation’s largest police department: The New York City Police Department spies on Muslims, which makes them less likely to trust police. That reinforces the belief that the community is secretive and insular, a key reason that current and former NYPD officials cite for spying in the first place.

The outreach campaign follows an Associated Press investigation that revealed the NYPD had dispatched plainclothes officers to eavesdrop in Muslim communities, often without any evidence of wrongdoing. Restaurants serving Muslims were identified and photographed. Hundreds of mosques were investigated, and dozens were infiltrated. Police used the information to build ethnic databases on daily life inside Muslim neighborhoods.

Many of these programs were developed with the help of the CIA.

At a recent “Know Your Rights” session for Brooklyn College students, someone asked why Muslims who don’t have anything to hide should avoid talking to police.

“Most of the time it’s a fishing expedition,” answered Ramzi Kassem, a law professor at the City University of New York, who supervises an advocacy organization that does such community presentations. “So the safest thing you can do for yourself, your family, and for your community is not to answer.”

New York Republican Rep. Peter King said this kind of reaction from the Muslim community is “disgraceful.”

Muslim groups have previously organized educational programs around the country describing a person’s legal rights, such as when they must present identification to a police officer and when they can refuse to answer police questions. A California chapter of a national Muslim organization posted a poster on its website that warned Muslims not to talk to the FBI. The national organization ultimately asked the California branch to remove the poster from the website.

In New York, the AP stories about the NYPD and internal police documents have outraged some Muslims and provided evidence of tactics that they suspected were being used to watch them all along. These disclosures have intensified the outreach campaigns in New York.

A recently distributed brochure from an advocacy organization at the City University of New York Law School warns people to be wary when confronted by someone who advocates violence against the U.S., discusses terror organizations, is overly generous or is aggressive in their interactions. The brochure said that person could be a police informant.

“Be very careful about involving the police,” the brochure said. “If the individual is an informant, the police may not do anything … If the individual is not an informant and you report them, the unintended consequences could be devastating.”

Sweeping skepticism of police affects community relations at all levels of law enforcement on a wide range of issues, not just the NYPD’s counterterrorism programs. Interactions with a real terror operative could go unreported to law enforcement out of an assumption that the operative is actually working for the NYPD. A victim of domestic abuse or street violence may not trust the police enough to call for help.

Retired New York FBI agent Don Borelli said intelligence gathering is key to police work, not just in terrorism cases. But he said it can backfire when people feel their rights are being violated.

“When they do, these kinds of programs are actually counterproductive, because they undermine trust and drive a wedge between the community and police,” said Borelli, now a security consultant with the Soufan Group.

Kassem said the activists’ presentations are intended to “inform citizens about their legal rights when law enforcement comes to their doorstep.” He said the goal is not to dissuade citizens from contacting authorities when they have concerns about a crime.

Since the 2001 terror attacks, the NYPD, city government officials and federal law enforcement have spent years building relationships with the New York Muslim community, assuring many Muslims that they are considered partners in the city’s fight against terrorism. But in some cases, community members who have been hailed as partners and even dined with Mayor Michael Bloomberg were secretly followed by the NYPD or worked in mosques that the department had infiltrated, according to secret NYPD documents obtained by the AP.

“There’s not a reference here to the fact that New York is the No. 1 target of Islamic terrorists, that the NYPD and the FBI have protected New York,” King said, referring to one of the recent brochures about detecting police informants.

King, chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, has held a series of hearings about the threat of radicalization within American Muslim communities and the level of cooperation members of the community provide to law enforcement. Muslim and civil rights advocacy groups have decried the hearings and pointed to terror cases around the country in which members of the Muslim community helped law enforcement foil plots.

New York Muslim community groups say they’ve held dozens of meetings for people who are worried about police surveillance and the NYPD’s counterterrorism programs. In one instance, an audience of college students watched as a law student played out the role of a police informant and another played the role of the person the informant was targeting. The goal was to teach people to spot informants.

“Stay away from these people. That’s one of the most powerful things you can do,” said Robin Gordon-Leavitt, a member of an advocacy organization Creating Law Enforcement Accountability and Responsibility.

At another meeting, organized by the Council on American-Islamic Relations, students watched a film of two actors portraying FBI agents talking their way into a young Muslim’s home and interrogating him. At the meeting, students were warned not to speak with police even if their parents, imams or Muslim clerics urge them to cooperate.

“You’ll even hear imams saying, ‘As long as I obey the law, I have nothing to worry about.’ But that’s not how it plays out on the ground,” said Cyrus McGoldrick, CAIR New York’s civil rights manager.

CAIR has had a strained relationship with law enforcement and was named an unindicted co-conspirator in a terrorist financing case.

The Muslim community wants an independent commission to investigate all NYPD and CIA operations in the Muslim community.

___

Sullivan reported from Washington. Associated Press writers Matt Apuzzo and Adam Goldman contributed to this report from Washington.