Imagine it is 5 a.m. and you’ve landed in New York after a 12-hour overseas flight. Standing in the line for U.S. citizens, you wait as a border agent asks passengers ahead a few cursory questions, then waves them through. Your family is instead ushered into a separate room for more than an hour of searching and questioning.

This was the welcome that Hassan Shibly, traveling with his wife and infant son, said they received in August 2010, when they returned to the United States from Jordan, after traveling to Mecca.

“Are you part of any Islamic tribe? Have you ever studied Islam full time? How many gods do you believe in?” “How many prophets do you believe in?” the agent at New York’s JFK Airport asked, according to Shibly, 24, a Syrian-born Muslim American. He said the agent searched his luggage, pulling out his Quran and a hand-held digital prayer counter.

“At the end — I guess (the agent) was trying to be nice — he said, ‘Sorry, I hope you understand we just have to make sure nothing gets blown up,’” said Shibly, a law school graduate who grew up in Buffalo.

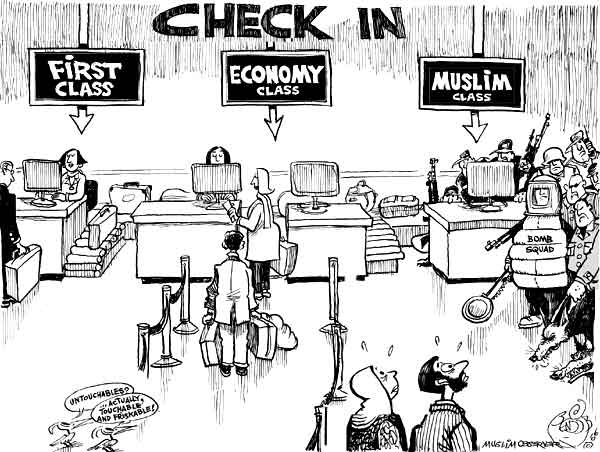

A decade after Islamic extremists used airplanes to attack the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Muslim American travelers say they are still paying the price for terror attacks carried out in the name of their religion. At airports, ports and land crossings, many contend, they are repeatedly singled out for special screening and intrusive questioning about their religious beliefs. Others say they have been marooned overseas, barred from flights to the United States.

‘Stories come pouring out’

“Whenever a group of Muslims sit together … stories come pouring out,” said real estate agent Jeff Siddique, a Pakistan-born U.S. citizen who has lived in Seattle for 35 years. “It’s story after story after story.”

That is supported by a survey released in August by the Pew Research Center, in which 36 percent of Muslim Americans who traveled by air in the last year said they had been singled out for special screening. The Transportation Security Administration does not keep detailed records, but a spokesman said that less than 3 percent of passengers receive a pat down, a primary form of secondary screening.

But while the U.S. Constitution prohibits discrimination according to religion, there is no way to determine whether the data supports the anecdotal evidence.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security releases only scant information on its anti-terrorism programs, including passenger screening, for security reasons. It has a clearly stated policy against racial and ethnic profiling, though it does encourage security personnel — both in Customs and Border Protection (CBP) which handles U.S. border entries, and in the TSA, which handles pre-flight screening — to focus on passengers’ connections to “countries associated with significant terrorist activity.”

The Justice Department, which sets the policy for Homeland Security, forbids racial and ethnic profiling. But if personnel are acting on specific intelligence, a certain group may be singled out. Justice Department guidance issued in 2003 gives this example:

“U.S. intelligence sources report that Middle Eastern terrorists are planning to use commercial jetliners as weapons by hijacking them at an airport in California during the next week. Before allowing men appearing to be of Middle Eastern origin to board commercial airplanes in California airports during the next week, (TSA and other agencies) may subject them to heightened scrutiny.”

But several civil rights groups say growing evidence points to targeting Muslims — and people who appear to be Muslim — without credible evidence of a crime or intent to commit one. In an array of legal cases, they are challenging the anti-terrorism bureaucracy to articulate its policy.

Among the questions they want answered: Is there a focus on Muslim travelers encoded in policy or encouraged by training? How do travelers end up on security watch lists, and is there any way to get off them? Does the U.S. government have the right to bar U.S. citizens from flying back into the country?

Rooting out ‘extremist tendencies’

The difficulty is knowing where policy ends and personal discretion kicks in.

For example, depending on how the directive to focus on travelers to and from countries with active terrorist organizations is interpreted, it might implicate a large swath of American Muslims. The majority of this population is made up of recent immigrants with connections to their countries of origin in the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia.

But Homeland Security recently launched an investigation of a flurry of complaints from Muslims who, like Shibly, say border agents went well beyond asking about their travels. Instead, the travelers say, they were questioned extensively about their religious beliefs and practices. Some reported being asked political questions, such as their views on the Iraq War or President Barack Obama.

One complaint filed by the nonprofit Council on American Islamic Relations with Homeland Security and the Justice Department said its Michigan branch alone has received “dozens of reports (from Muslim travelers) … that CBP agents pointed firearms at them, detained and handcuffed them without predication of crimes or charges, and questioned them about their worship habits.”

Shibly’s case is one of five included in a separate complaint filed by the the nonprofit Muslim Advocates and the American Civil Liberties Union in December.

Another case detailed in the complaint is that of New Jersey resident Lawrence Ho, who says that when he reached the U.S. border from Canada by car in February 2010 he was surprised to find the border agent knew that he had converted to Islam. Ho, who is Chinese American, said the border agent questioned him for nearly four hours about his Muslim beliefs. But an email to the CBP to complain about the encounter at the Rainbow Bridge checkpoint in New York didn’t get far.

“In 2001, the U.S. was attacked by Islamist extremists,” wrote a senior CBP officer in an email response to Ho. “If a CBP officer inquires as to a person’s religious beliefs in order to uncover signs of extremist tendencies, that officer is well within his authority.”

It is not clear if that statement is in line with Homeland Security policy. In response to msnbc.com queries, Homeland Security did not offer any detail about the ongoing investigation, but provided a general statement by email.

A group of Washington residents prays at the U.S.-Canada border near Blaine, Wash., on April 17, during a protest of alleged discriminatory treatment of Muslims returning to the United States. From left are organizer Jeff Siddique, Jeremy Mseitif, John Baker and Arsalan Bokhari.

“DHS does not tolerate religious discrimination or abusive questioning – period,” wrote Homeland Security spokesman Chris Ortman. The department’s office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties “has notified the complainants and their representatives that it will investigate these allegations and, if appropriate, the department will take corrective action.”

The ACLU and Muslim Advocates also filed a Freedom of Information Act request, seeking all records, standards and statistics pertaining to CBP questioning on religious and political beliefs and practices, border training programs and disclosure of how the travelers’ information is used.

“We hope … (DHS) will condemn the practice of asking any citizen or legal resident of the U.S. about their religious beliefs, political beliefs and religious practices,” said ACLU staff attorney Nusrat Choudhury. “We also hope that (it) will note the troubling nature of the fact that so many Muslim legal residents or citizens are being asked these kinds of questions.”

Behavior spotters

Screening is a multi-layer process, with decisions made at the federal level all the way down to the individual agent at the X-ray machine.

According to a spokesman for the TSA, some people are chosen randomly for secondary search, while others merit secondary screening if their luggage contains things that raise questions. The TSA is now adding a program called SPOT — Screening Passengers by Observation Technique.

“We have behavior detection officers who are all over the airport, looking for people exhibiting behaviors that are considered anomalous … doing things that suggest they’re trying to hide something,” said TSA spokesman Nick Kimball. “They are observing the queue. When that person gets up to the front, they would be referred to the side.”

The TSA website calls the program “a positive step that does not require ethnic profiling but looks to the pattern of behavior. … These are tools that would allow us to be more precise, but without getting into racial profiling, which is a bad thing.”

The TSA is also required to conduct secondary screening according to two lists — the “no-fly” list and the “selectee” list, which are provided by the Terrorism Screening Center, a division of the FBI.

The screening center says there are 16,000 individuals — including about 500 U.S. citizens — on the no-fly list, which bars the individuals on it from flying to, from or within the United States. Another 16,000 are on the selectee list, which triggers secondary screening.

Both are subsets of a consolidated watch list called the Terrorism Screening Database of “known or appropriately suspected terrorists.” The number of names in the database fluctuates, but at present it names 420,000 individuals, about 2 percent of them Americans, the screening center says. The FBI distributes relevant subsets of the database to different frontline agencies such as TSA, CBP, financial watchdogs and law enforcers. Even people stopped for traffic violations can be quickly checked against the list.

Each agency “must comply with the law, as well as its own policies and procedures to protect privacy rights and civil liberties,” the screening center said.

The effectiveness of the lists came into question after an attempted bombing of an airliner on Christmas Day 2009, when Nigerian Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who was not on either watch list, tried to detonate plastic explosives on a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit. Ultimately he hurt only himself, but the scare prompted the screening center to expand the criteria it uses to populate the no-fly list.

By design, none of the criteria that land an individual in the database or on the watch lists is made public.

“People are put on the watch list based on a series of criteria,” said Sheldon Jacobson, a security expert and computer science professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Nobody really knows them. They are very secret and they keep evolving. In many ways (the government) has to keep it private because if they give it out, people will game the system.”

That secrecy presents a conundrum for many people who believe they are on a list and do not belong there.

Some of the cases involve mistaken identity because a traveler possesses a common name like Mohammad — the Arabic equivalent of Smith. As a result, some civil rights lawyers believe that the lists affect two to three times as many fliers as are legitimately on them.

Marooned

One of the most chilling cases surrounding the no-fly list is that of Gulet Mohamed, a 19-year-old American citizen of Somali heritage.

Mohamed had been visiting family in Yemen and Somalia — two countries with active Islamist terrorist groups. When he went to the Kuwait airport to extend his visa in December, he was arrested and taken to a detention facility, where he was blindfolded, questioned and beaten by unknown agents, according to his lawyer, Ghadeir Abbas.

The questioners were especially interested in information about Anwar al-Awlaki, a dual U.S. and Yemeni citizen turned Islamic extremist in Yemen, Abbas said. Mohamed insisted he had no information and, after a week, Kuwait ordered his deportation.

But when he tried to board a flight to the United States, he was told he was on the no-fly list. Only after Abbas filed a lawsuit on his behalf in January was Mohamed allowed to return home to Virginia.

Mohamed is pursuing a claim for damages and to be removed from the list. The federal government wants the case thrown out on the grounds that it is irrelevant now that he is back in the U.S. Meantime, it will not confirm if he is on the no-fly list. The lawsuit is pending, after a judge moved it to a circuit court on jurisdictional grounds.

“It’s this very Kafkaesque world where no one has charged (people on the list) with any crime … but they can see its effects,” said Abbas, an attorney with CAIR. “… His case is the most heinous example of what the no-fly list can do.”

Other pending court cases allege that Muslim American travelers have encountered similar violations of their rights, including some who were forced to take thousand-mile circuitous land routes to get back into the U.S. or were stuck overseas for weeks or months until lawyers here took up their cases.

The ACLU, which argues that the watch list system is unconstitutional, has filed a lawsuit against the Justice Department, the FBI and the Terrorist Screening Center naming 20 people — 18 U.S. citizens and two permanent residents — who allegedly have been prevented from boarding airline flights to or from the U.S. The plaintiffs say they were told by security or airline staff that their names were on the no-fly list.

“Thousands of people have been barred altogether from commercial air travel without any opportunity to confront or rebut the basis for their inclusion, or apparent inclusion” on the no-fly list,” the lawsuits says. “The result is a vast and growing list of individuals whom, on the basis of error or innuendo, the government deems too dangerous to fly, but too harmless to arrest.”

In response, the government objected on jurisdictional grounds and argued that the policy does not violate the constitutional rights of the travelers because “they have not been denied the right to re-enter and reside in the United States, nor have they been denied the ability to travel.”

But critics of the list note that in cases like that of the lead plaintiff, Ayman Latif, a 33-year-old U.S. citizen and disabled Marine Corps veteran, that would have meant weeks of travel from the Middle East to the United States by sea and land, at considerable additional expense.

The U.S. District Court in Portland, Ore., dismissed the case on jurisdictional grounds, ruling that it should go instead to an appeals court. The ACLU is appealing that decision.

Double and triple checked

Names on the selectee list also are not public, but travelers can surmise they are on it if, like Hassan Shibly, they are repeatedly singled out for secondary screening.

Here’s how it usually plays out, according to Shibly: When he prepares to fly, the computer system prevents him from checking in online. Airport kiosks will not process his boarding pass and instead instruct him to see an agent. The agent types in his name, and then calls a phone number. The agent and Shibly wait for up to 20 minutes for a response. Only then does he typically receive a boarding pass.

After that, Shibly usually gets pulled out of line for a pat down at the TSA screening point. On some flights, there is a final check-in by the airline employee taking boarding passes at the gate.

And when he returns to the U.S., Shibly said, he encounters more special screening.

CBP documents obtained via a FOIA request by Muslim Advocates show that Shibly has been pulled aside for secondary screening at border points at least 20 times since 2004.

Shibly said he has jumped through extra hoops so many times now that he is surprised by exceptions.“Twice I was able to print my boarding pass at the kiosk. It was great,” he said.

Is relief on the way?

Over time, federal security officials have tried a number of different programs geared to cut down on screening of travelers who don’t pose a security threat.

The Travel Redress Inquiry Program, or TRIP, introduced in 2007, allows travelers who think they have been wrongly placed on a list to file an online grievance for the review of their cases. In response, TRIP applicants receive a letter stating that Homeland Security has corrected any problems it found, though it does not confirm whether the person was on a list or not, or that there was a problem.

But the jury remains out. TRIP may be addressing cases of mistaken identity — in which a person is targeted because their name matches that of a legitimate suspect — but critics say it apparently doesn’t allow an individual on the no-fly or selectee lists to dispute why they are included.

A program called SECURE, adopted by TSA in November 2010, adds another layer of behind-the-scenes cross referencing to reduce cases of mistaken identity.

‘Roach motel’

With the introduction of TRIP and SECURE, some Muslim Americans report fewer hassles, but it’s easy to find exceptions.

Sayeed “Syd” Rahman, a consultant in Herndon, Va., said he applied for a redress number in 2009 after pre-flight screening made him miss his flight.

But he has seen no change.

“This is in spite of getting a redress number,” said Rahman. “And in spite of being in the U.S. for 35 years, in spite of having a wife who is American and a son who actually qualifies as a Son of the American Revolution.”

Rahman says that until recently he even had Department of Defense clearance for work that involved the military.

“This list … is like a roach motel. You can check in but you can’t check out,” said Rahman.

Immediately after 9/11, profiling was the biggest problem for Muslim travelers, said attorney Banafsheh Akhlagi, a civil rights expert who has handled several thousand discrimination complaints in the past decade.

Now, she believes there are many factors causing travelers’ woes, including a complex web of security policies built over the past decade and immense pressure on frontline personnel not to miss a threat.

“Here we are 10 years later and we are discovering that there is no uniformity in the way in which the Department of Justice applies the law at every level,” said Akhlaghi. “They administer an edict that gets funneled down to border security and TSA, who are then charged with enforcing these policies which they may not understand without the necessary training. As a result, these individuals, due to government pressure, are interpreting and enforcing the laws with more gravity than the law was originally intended to do.”

But Jacobson, the security expert, said the inconvenienced travelers aren’t the only ones suffering.

“I’m sympathetic to all people involved, both those who are subject to too much screening and to the screeners,” he said. “Quite frankly, it’s a hard job.”