John Phillip Walker Lindh, my son, was raised a Roman Catholic, but converted to Islam when he was 16 years old. He has an older brother and a younger sister. John is scholarly and devout, devoted to his family, and blessed with a powerful intellect, a curious mind, and a wry sense of humour.

Labelled by the American government as “Detainee 001” in the “war on terror”, John occupies a prison cell in Terre Haute, Indiana. He has been a prisoner of the American government since 1 December 2001, less than three months after the terror attacks of 9/11.

John is entirely innocent of any involvement in the terror attacks, or any allegiance to terrorism. That is not disputed by the American government. Indeed, all accusations of terrorism against John were dropped by the government in a plea bargain, which in turn was approved by the US district court in which the case was brought.

Despite its proud history as a stable constitutional democracy, the US has, for 10 years, been affected by post-traumatic shock, following the horrific events of 11 September 2001. I can find no other explanation for the barbaric mistreatment and continued detention of a gentle young man like John Lindh.

John Walker Lindh, aged 15, with his father, Frank, on a family holiday, 1996. Photograph courtesy of Lindh family

John is blessed with a calm and curious nature. As a child, he was more sceptical than our other two children about such things as Santa Claus. When he was 12 years old, he saw the film Malcolm X, and was moved by its depiction of the pilgrims in Mecca. He began to explore Islam and, four years later, decided to convert.

What attracted John to Islam, I think, was the simplicity of its beliefs, and the authenticity of its source documents – the Qur’an and Hadith. It appealed to his intellect as well as his heart. To me and to John’s mother, his conversion was a positive development and certainly not a source of worry. I once told him I felt he had always been a Muslim, and only needed to find Islam in order to discover this in himself. He remained the loving son and brother he had always been. There was never a breach of any kind between us.

John had always been a good student, but his study habits improved after his conversion. He immersed himself in Islamic literature, and quickly came to the conclusion that he needed to learn Arabic in order to continue his studies.

In 1998, at the age of 17, John left home in California and travelled to Sana’a, the ancient capital of Yemen, where he embarked on a rigorous course of study. He was determined not only to become fluent in Arabic, but also to pursue an education in the old traditions of Islam. He returned home briefly in 1999, and then returned to Yemen in February 2000, just before his 19th birthday. John’s mother and I supported him, emotionally and financially. He remained in close contact with us and with his sister and brother while overseas.

In September 2000, John told me he intended to continue his studies in Pakistan, focusing on Arabic grammar and Qur’an memorisation. I wrote back: “I trust your judgment and hope you have a wonderful adventure.” He arrived in Pakistan in November 2000 and enrolled in a Qur’an memorisation programme in a madrasa.

John’s letters home showed passionate enthusiasm for both Yemen and Pakistan. He loved the cultures he discovered in both countries. He was a Muslim in a Muslim world.

In late April 2001, John wrote to me and his mother, saying he planned to go into the mountains to escape the oppressive summer heat. We had no further contact from him for seven months. Unbeknown to us, he crossed the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan, with the intent of volunteering for service in the Afghan army under the control of the Taliban government.

John’s mother and I grew increasingly worried as the summer passed. John had warned us that there might be gaps in his contact with us, as there were no internet cafes in the mountains of Pakistan from which to send emails. But we did not anticipate such a complete lapse in correspondence from him. We also never guessed he was in Afghanistan rather than Pakistan. John’s mother, especially, was frantic with worry as the months passed with no word from him.

At that time, the Taliban governed most of Afghanistan, and were engaged in a long-running civil war against a Russian-backed insurgency known euphemistically as the Northern Alliance. John was quickly accepted as a volunteer soldier, and received two months of infantry training in a Taliban military camp before being dispatched to the front lines.

Rohan Gunaratna, an international terrorism expert and author of the book Inside Al-Qaeda: Global Network of Terror, conducted a lengthy interview with John, and prepared a written report for the American court to which John was brought for trial. Gunaratna is an expert consultant to the US government itself on terrorism matters. “Those who, like Mr Lindh, merely fought the Northern Alliance,” he wrote, “cannot be deemed terrorists. Their motivation was to serve and to protect suffering Muslims in Afghanistan, not to kill civilians.”

John described his motivation in similar terms. “I felt,” he later explained to the court, “that I had an obligation to assist what I perceived to be an Islamic liberation movement against the warlords who were occupying several provinces in northern Afghanistan. I had learned from books, articles and individuals with first-hand experience of numerous atrocities committed by the Northern Alliance against civilians. I had heard reports of massacres, child rape, torture and castration.”

To the western world, and to me as John’s father after I learned where he had been, this was misplaced idealism. John’s decision to volunteer for the army of Afghanistan under the control of the Taliban was rash, and failed to take into account the Taliban’s mistreatment of its own citizens. But his assessment of the Northern Alliance warlords was neither exaggerated nor inaccurate. The brutal human rights violations committed by the Northern Alliance were thoroughly documented in the US department of state’s annual human rights reports throughout the 90s. They did indeed include massacres, rape (of both women and children), torture and castration.

John’s impulse was to help. In doing so, he was responding not only to his own conscience, but to a central tenet of the Islamic faith, which calls upon able-bodied young men to defend innocent Muslim civilians from attack, through military service if necessary. This is not “terrorism” at all, but precisely its opposite.

From the time of the Soviet invasion in 1979, tens of thousands of young Muslim men from all over the world had volunteered, as John did, for military service in Afghanistan. It was comparable to the influx of young volunteer soldiers in support of the republic of Spain during the Spanish civil war.

These young soldiers performed heroically in the defeat of the Soviet Union. Their cause was openly supported by the American government itself, particularly during the administration of President Ronald Reagan, who took office two weeks before John’s birth in early 1981.

In March 1982, President Reagan declared: “Every country and every people has a stake in the Afghan resistance, for the freedom fighters of Afghanistan are defending principles of independence and freedom that form the basis of global security and stability.” In March 1983, he cited “the Afghan freedom fighters” as “an example to all the world of the invincibility of the ideals we in this country hold most dear, the ideals of freedom and independence”. In a March 1985 speech, he said: “They are our brothers, these freedom fighters, and we owe them our help… They are the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers and the brave men and women of the French resistance. We cannot turn away from them.”

Given the history of US involvement in Afghanistan, it would seem absurd to suggest that John Lindh was being disloyal to America when he went into Afghanistan in 2001 and joined the army there. If the march of history could be arrested in the spring or summer of 2001, John’s odyssey might be regarded as quixotic and unusual for a young American, but not in the least bit sinister, and certainly not criminal in nature. In fact, John’s concern about the suffering of people in Afghanistan was shared by his own government. On 21 July 2000, for example, the US department of state issued a “fact sheet” that reported that the US was “the largest single donor of humanitarian aid to the Afghan people”.

The US also provided substantial economic assistance directly to the Taliban government. In May 2001, for example, the American government under President George W Bush announced a grant of $43m to the Taliban government for opium eradication. Secretary of State Colin Powell personally announced the grant himself in a press release and pledged: “We will continue to look for ways to provide more assistance to the Afghans.” The New York Times called this “a first, cautious step toward reducing the isolation of the Taliban” by the new Bush administration.

This is not to suggest the US was entirely friendly with the Taliban. In 1999, President Clinton placed the Taliban government under economic sanctions as a consequence of its human rights violations, particularly against women. But there were no hostilities between the US and the Taliban, and by 2001 relations were improving.

In his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell describes a nightmarish world of perpetual war, in which two massive nations, Oceania and Eastasia, are aligned against a third nation state known as Eurasia. The alliance between Oceania and Eastasia ends, and Eastasia then begins fighting alongside Eurasia against Oceania. In what Orwell famously called “doublethink”, the population of Oceania then is taught to believe “we have always been at war with Eastasia”.

Something eerily similar happened in the US after 9/11. Thirty years of American policy abruptly changed and America swung to the opposite side. The Taliban became our enemy. “They have always been our enemy” is what people in America came to believe.

In October 2001, the US invaded Afghanistan and aligned itself with the Northern Alliance in order to oust the Taliban government. Colin Powell’s April press release was quietly removed from the state department’s website.

In early September 2001, days before the 9/11 attacks, John arrived at his military post in the province of Takhar in the far north-eastern corner of Afghanistan, near the border of Tajikistan. This was the frontline in the civil war between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance. John was issued with a rifle and two hand grenades – standard issue for an infantry soldier. He performed sentry duty and did some cooking for the Taliban troops. He never used his weapons. He served with a number of other foreign volunteer soldiers. They were called Ansar, an Arabic term meaning “helpers”.

The training camp in Afghanistan where the Ansar received their infantry training was funded by Osama bin Laden, who also visited the camp on a regular basis. He was regarded by the volunteer soldiers as a hero in the struggle against the Soviet Union. These soldiers did not suspect Bin Laden’s involvement in planning the 9/11 attacks, which were carried out in secret. John himself sat through speeches by Bin Laden in the camp on two occasions, and actually met Bin Laden on the second such occasion. John has said he found him unimpressive.

After 9/11, America’s intelligence agencies came under intense scrutiny for their failure to anticipate and prevent the attacks, and their apparent inability to track down Osama bin Laden. It is a curious fact of history that John Lindh, an idealistic 20-year-old Californian, suspecting nothing of bin Laden’s connections to terrorism, was able without difficulty to meet this notorious figure in the summer of 2001. Why American intelligence agents were unable to do so remains unexplained. John himself did not believe he was encountering a terrorist. John knew only that bin Laden had been generous in funding the military camp, and he was able to discern that Bin Laden was not a legitimate scholar or leader in the traditions of Islam.

The American invasion of Afghanistan commenced in October 2001. Few American troops were deployed in the northern reaches of Afghanistan. The Americans relied on Northern Alliance forces as their proxy, combined with aerial bombing, to displace the Taliban forces.

The front between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance in Takhar where John was stationed quickly dissolved after the bombing commenced. Taliban troops fled in panicked retreat to Kunduz. They marched without stop for two days, covering a distance of 50 miles of harsh, desert terrain. The conditions were hellish. The Northern Alliance troops killed all stragglers who fell behind, often castrating them before killing them.

The soldiers at Kunduz who wished to surrender faced a terrible dilemma. For years it had been the practice of the Northern Alliance to torture and murder prisoners of war. These crimes were legendary and well known to both the Taliban soldiers and the US government.

John’s lawyers later obtained from the American government an unclassified cable sent from the US embassy in Kunduz on 20 November 2001, to Colin Powell and the joint chiefs of staff. The cable was labelled “priority”. It bore the subject line: “Kunduz representatives appeal for a bombing halt during surrender negotiations.” It said that, according to local authorities in Kunduz, Taliban soldiers trapped in Kunduz “wanted to surrender to someone who would not kill them”. This was described as a “sticking point” in the surrender negotiations. The Taliban, according to the cable, had “proposed surrendering to the US or the UN”. The cable confirmed that the American authorities had informed their counterparts in Kunduz that “neither was a realistic option and suggested that they seek the [Red Cross’s] involvement if they had not done so already”.

On 21 November 2001, the regional Taliban military leader, Mullah Fazel Mazloom, entered into face-to-face surrender negotiations with General Abdul Rashid Dostum of the Northern Alliance. The pact was destined not to end well. Dostum was a notorious figure who had served as an officer in the Soviet occupation government. Troops under Dostum’s command were believed responsible for the mass execution of an alleged 2,000 Taliban prisoners captured near Mazar-i-Sharif in 1997. The New Yorker magazine has referred to Dostum as “perhaps Afghanistan’s most notorious warlord”, a man who is “viewed by most human rights organisations as among the worst war criminals in the country”.

Nonetheless, a bargain was reached in which Dostum demanded and received a large cash payment, then agreed to grant approximately 400 disarmed Taliban soldiers safe passage through Dostum-controlled territory to the city of Herat. John, in haggard condition after the march through Takhar, was among those 400 troops.

The Taliban soldiers had no sooner laid down their arms when Dostum breached the agreement. Instead of the safe passage they had been promised, the soldiers were loaded into trucks and diverted to the ancient Qala-i-Jangi fortress on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif. As the prisoners were being unloaded in the courtyard, John heard a loud explosion when one of the prisoners detonated a grenade that he had concealed. Two of Dostum’s men were killed in the blast.

Dostum’s soldiers quickly regained control, but they were infuriated. The prisoners were crowded into the basement of a sturdy, pink Soviet-built classroom building adjacent to a horse pasture. The “pink building”, as it became known, was at the centre of the events that unfolded over the next seven days. It was dark in the basement rooms into which the 400 men were crowded. To retaliate for the earlier attack, Dostum’s men dropped a grenade down an air duct that wounded or killed several prisoners, narrowly missing John, who spent the night crouched in a corner unable to sleep.

The next morning, Sunday 25 November, was sunny and warm at the Qala-i-Jangi fortress. Video footage shows a seemingly calm scene as the prisoners, with arms tied behind backs, are led out of the basement and made to kneel in rows in the horse pasture beside the pink building. The main sound on the film is the chirping of hundreds of birds. Dostum’s men were rough. Some prisoners were kicked and beaten with sticks. John was hit in the back of the head and nearly knocked unconscious. Nonetheless, he hoped they would be released for the agreed upon journey to Herat.

Although there were no US or British troops at the fortress that morning, two American intelligence agents were present, dressed in civilian clothes. They circulated among the prisoners, occasionally giving instructions to Dostum’s guards. One of them, Dave Tyson, was dressed in a long Afghan shirt and carried a large gun and a video camera. The other, Johnny “Mike” Spann, a former marine, was dressed in a black shirt and jeans. He was also armed. As they moved among the prisoners, they singled out captives for interrogation. They never identified themselves as American agents, and so they appeared to John and the other prisoners to be mercenaries working directly for General Dostum.

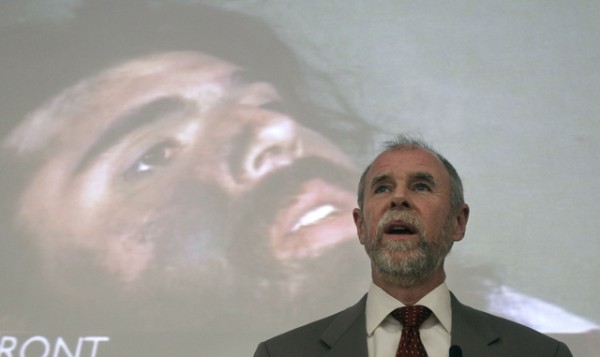

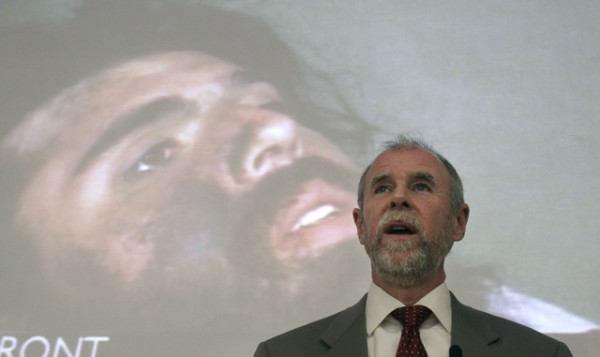

John was spotted and removed from the body of prisoners for questioning. The moment was recorded on video and later seen by millions on television.

In the video, John sits mutely on the ground as he is questioned about his nationality.

“Irish? Ireland?” Spann asks.

John remains silent.

John Walker Lindh at the Qala-i-Jangi fortress on 3 December 2001, awaiting treatment from the Red Cross, having been captured by US forces. Photograph: James Hill/Getty Images

“Who brought you here?… You believe in what you are doing that much, you’re willing to be killed here?”

Still no reply.

Tyson to Spann [for John’s benefit]: “The problem is, he’s got to decide if he wants to live or die, and die here. We’re just going to leave him, and he’s going to [expletive] sit in prison the rest of his [expletive] short life. It’s his decision, man. We can only help the guys who want to talk to us. We can only get the Red Cross to help so many guys.”

I think it was apparent that Spann and Tyson were American agents, but because they were in the company of Dostum’s forces, unaccompanied by American troops, it clearly was not safe for John to talk to them. They meant business when they said John might be killed by Dostum, and that the Red Cross could only “help so many guys”. John was in extreme peril at that moment, and he knew it.

John was then returned to the main body of prisoners, while others were still being brought out of the basement and forced to kneel in the horse pasture. Then, suddenly, there was an explosion at the entrance to the basement, shouts were heard, and two prisoners grabbed the guards’ weapons. According to Guardian journalist Luke Harding’s account: “It was then… that Spann ‘did a Rambo’. As the remaining guards ran away, Spann flung himself to the ground and began raking the courtyard and its prisoners with automatic fire. Five or six prisoners jumped on him, and he disappeared beneath a heap of bodies.”

Spann’s body was later recovered by US special forces troops. He was the first American to die in combat in the American–Afghan war. He was buried with full military honours at Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington.

As soon as the uprising began, the Northern Alliance guards turned their weapons on the 400 bound prisoners, killing or severely wounding scores of them. Some prisoners tried to stand and run; they were gunned down. It was a slaughter. John tried to run, but he was shot in the right thigh and fell to the ground. For the next 12 hours he lay motionless, pretending to be dead.

There were two groups of Taliban prisoners in the fortress: those who chose to fight and those who hunkered down in the basement of the pink building and tried to survive. John was in the latter group. The prisoners who fought put up a fierce resistance, looting buildings for weapons and ammunition, firing from windows, rooftops, and ditches. Using a satellite phone, Dave Tyson, who had just seen his colleague killed, telephoned the US embassy in Tashkent, shouting: “We have lost control. Send in helicopters and troops.” US air controllers stationed outside the fortress walls called in air strikes, which struck with devastating impact inside the fortress.

More air raids were staged the next day, Monday, when a massive 2,000lb bomb was dropped. It missed its intended target, the pink building, and hit Dostum’s soldiers. This “friendly fire” incident brought an end to the air strikes. For John and the other Taliban soldiers holed up in the basement of the pink building, the percussive effect of the bomb shook them to their bones and left them trembling.

By Wednesday, the last of the resisting Taliban fighters had been killed, and Dostum’s soldiers were once again in full control of the fortress. Luke Harding was allowed into the compound along with some other journalists, and he found a horrific scene: “We had expected slaughter, but I was unprepared for its hellish scale… It was hard to take it all in. The dead and various parts of the dead… turned up wherever you looked: in thickets of willows and poplars; in waterlogged ditches; in storage rooms piled with ammunition boxes.” Harding observed that many of the Taliban prisoners had died with their hands tied behind their backs.

On Wednesday and Thursday, Dostum’s troops engaged in a sustained effort to kill the Taliban survivors who remained in the basement of the pink building, which they were afraid to enter themselves. More grenades were dropped down the air ducts and RPGs were fired directly into the basement. John received shrapnel wounds in his shoulder, back, ankle and calf, in addition to the bullet still lodged in his thigh. At one point, fuel was poured down the air ducts and a fire was ignited in which some fuel-drenched prisoners were burned to death. John, choking on the black smoke, lost consciousness. He awoke with the taste of gasoline in his mouth and loud explosions in the hall, as more rockets and grenades ricocheted through the basement.

On Friday, Dostum’s troops tried yet another tactic. They flooded the basement with cold water. Unable to stand on his own, John braced himself on a stick and a fellow soldier for the next 24 hours to avoid drowning in the waist-deep water, which was full of blood and waste. The next morning no one inside the fortress thought it possible that anyone was still alive in the pink building, but 86 of the prisoners had managed to survive the week-long ordeal. One of them was John Lindh.

On Saturday 1 December, the Red Cross arrived at the fortress and the survivors, who for several days had been trying to surrender, were finally allowed to exit the basement. When they emerged into the bright sunlight, they encountered a confusing horde of journalists, Red Cross workers, Dostum’s soldiers, and British and American troops.

That evening John and the other survivors were taken to a prison hospital in Sheberghan. Although wet and cold from the flooding of the basement, they were transported in open bed trucks in the frigid night air. At Sheberghan, John was carried on a stretcher and set down in a small room with approximately 15 other prisoners. CNN correspondent Robert Pelton came in accompanied by a US special forces soldier and a cameraman. Despite John’s protests, Pelton persisted in filming John and asking questions as an American medical officer administered morphine intravenously. By the time he departed a short time later, Pelton had captured on videotape an interview in which John said that his “heart had become attached” to the Taliban, that every Muslim aspired to become a shahid, or martyr, and that he had attended a training camp funded by Osama bin Laden.

The CNN interview became a sensation in the US. By mid-December, virtually every newspaper in America was running front-page stories about the American Taliban, and the broadcast media were saturated with features and commentary about John. Here was a “traitor” who had “fought against America” and aligned himself with the 11 September terrorists. Newsweek magazine published an issue with John’s photograph on the cover, under the caption “American Taliban”.

Beginning in early December, President Bush, vice-president Dick Cheney, members of the cabinet and other officials then embarked on a series of truly extraordinary public statements about John, referring to him repeatedly as an “al-Qaida fighter”, a terrorist and a traitor. I think it fair to say there has never been a case quite like this in the history of the US, in which officials at the highest levels of the government made such prejudicial statements about an individual citizen who had not yet been charged with any crime.

I will offer only a small sample of these statements. In an interview at the White House on 21 December 2001, President Bush said John was “the first American al-Qaida fighter that we have captured”. Donald Rumsfeld, secretary of defence, told reporters at a press briefing that John had been “captured by US forces with an AK-47 in his hands”. Colin Powell, secretary of state, said John had “brought shame upon his family”. Rudy Giuliani, New York mayor, remarked: “I believe the death penalty is the appropriate remedy to consider.”

John Ashcroft, the US attorney general, staged two televised press conferences in which he accused John of attacking the US. “Americans who love their country do not dedicate themselves to killing Americans,” he declared.

A federal judge took the unusual step of writing to the New York Timescriticising the attorney general for violating “Justice Department guidelines on the release of information related to criminal proceedings that are intended to ensure that a defendant is not prejudiced when such an announcement is made”.

Even the ultra-conservative National Review thought Ashcroft had gone too far in making such prejudicial comments about a pending prosecution. It criticised the comments as “inappropriate” and “gratuitous”, stating that in the future “it would be better for the attorney general simply to announce the facts of the indictments, and to avoid extra comments which might unintentionally imperil successful prosecutions”.

I am a lawyer, trained in the law, with more than 25 years of experience. Never have I seen or read about a case in which a person accused of a crime was so conspicuously deprived of what we call “the presumption of innocence”. On the contrary, my son was presumed guilty, not only by government officials but by the entire mainstream journalism and media establishment in America. It was – and still is – widely reported in America that John Lindh is a “terrorist” who fought against the US.

Our lives back home were completely upturned by the sudden and pervasive notoriety of John’s case. We found ourselves dodging television cameras and reporters. In the first couple of days after John’s capture, I appeared on several news programmes in an effort to explain who John was and to ask for mercy. My sense of privacy and anonymity were at least temporarily destroyed.

All of us in John’s family also were wracked with anxiety about John’s own physical and emotional wellbeing. We had no source of information about John from within the government itself. They were holding our son incommunicado, even as President Bush and other officials made repeated statements about him. Anything we were able to learn about John came from the news media, not from the government.

Happily, our neighbours, friends, co-workers and even strangers in California were uniformly warm and supportive towards me, John’s mother and our other children. One Sunday, on my way to church, a friendly stranger stopped his car and shouted to me: “How’s John?”

John Walker Lindh’s father, Frank, and mother, Marilyn, outside the courthouse in Alexandria, Virginia, 2002. Photograph: Hillery Smith Garrison/AP

Another enormous source of comfort to us came from James Brosnahan, a distinguished and courageous trial lawyer in San Francisco who agreed to represent John. On 3 December, Brosnahan took up his case, and from that day forward we had a valiant defender in him and the other lawyers who worked on the defence team. It felt as if a protective shield had been constructed around John and all of us in the family.

Once John was in the custody of the US military, the US government had to decide what to do with him. The FBI has estimated that during the 90s as many as 2,000 American citizens travelled to Muslim lands to take up arms voluntarily, and that as many as 400 American Muslims received training in military camps in Pakistan and Afghanistan. None of these American citizens was indicted, or labelled as traitor and terrorist. They were simply ignored by their government, which made no attempt to interfere with their travel. But the 9/11 attacks changed everything, and it was the timing of John’s capture that contributed to his fate. It soon became apparent to me that, rather than simply repatriate my wounded son, the government was intent on prosecuting him as a “terrorist”.

In the days and weeks that followed, John endured abuse from the US military that exceeded the bounds of what any civilised nation should tolerate, even in time of war. Donald Rumsfeld directly ordered the military to “take the gloves off” in questioning John.

On 7 December, wounded and still suffering from the effects of the trauma at Qala-i-Jangi, John was flown to Camp Rhino, a US marine base approximately 70 miles south of Kandahar. There he was taunted and threatened, stripped of his clothing, and bound naked to a stretcher with duct tape wrapped around his chest, arms, and ankles. Even before he got to Camp Rhino, John’s wrists and ankles were bound with plastic restraints that caused severe pain and left permanent scars – sure proof of torture. Still blindfolded, he was locked in an unheated metal shipping container that sat on the desert floor. He shivered uncontrollably in the bitter cold. Soldiers outside pounded on the sides, threatening to kill him.

After two days in these circumstances, John was removed from the shipping container and taken into a building at Camp Rhino. When his blindfold was removed, John found himself in front of a man who identified himself as an FBI agent and then read from an advice-of-rights form. When the agent reached the part that concerned right to counsel, he said: “Of course, there are no lawyers here.” John was not told his mother and I had retained an attorney for him who was ready and willing to travel to Afghanistan. Worried that he would be returned to the shipping container if he did not sign the form, John signed the waiver.

A lengthy interrogation followed, after which US military personnel put John back in the metal shipping container, although this time his leg restraints were loosened and he was no longer bound by duct tape or blindfolded. On 14 December, he was placed on board the USS Peleliu, where navy physicians observed that he was suffering from dehydration, hypothermia, and frostbite, and that he could not walk. On 15 December, the bullet was finally removed from his leg in a surgical procedure – more than two weeks after he had been transferred to the custody of the US military. The doctor who removed the bullet later told John’s lawyers there had been little or no healing of the wound, which he attributed to malnutrition and cold.

In June 2002, Newsweek obtained copies of internal email messages from the justice department’s ethics office commenting on the Lindh case as the events were unfolding in December 2001. The office specifically warned in advance against the interrogation tactics the FBI used at Camp Rhino, and concluded that the interrogation of John without his lawyer present would be unlawful and unethical. This advice was ignored by the FBI agent who conducted the interrogation.

Interestingly, in an 10 December email, one of the justice department ethics lawyers noted: “At present, we have no knowledge that he did anything other than join the Taliban.”

The government brought 10 counts against John in its overblown indictment. “If convicted of these charges,” attorney general Ashcroft boasted, “Walker Lindh could receive multiple life sentences, six additional 10-year sentences, plus 30 years.” The most serious count was a charge of conspiracy to commit murder in connection with the death of Mike Spann. The charge was groundless: the prisoner uprising at the Qala-i-Jangi fortress had been spontaneous and John was also a victim, not a participant.

John arrived back in the US on 23 January 2002 in chains aboard a military plane that landed at Washington Dulles International airport. The government selected Dulles so they could bring charges against John in northern Virginia, near the Pentagon (one of the 9/11 targets), where hostility against John was assured. He was flown by helicopter to the Alexandria City Jail. John’s mother and I tried to visit him that night, along with the lawyers we had retained for him, but we were turned away. We finally were able to see our son the next morning in a holding cell on the first floor of the US courthouse. His lawyers met him only briefly before his first appearance in the court that morning.

The case of United States of America v John Philip Walker Lindh was set for trial before Judge T S Ellis III. On 24 January, the judge announced he was setting a trial date for late August. We were horrified, as this would ensure that John would be on trial on the first anniversary of 9/11. It would be hard to conceive of a more prejudicial circumstance for a criminal defendant, especially in the wake of the intemperate statements attorney general Ashcroft had made in his two press conferences.

John’s lawyers filed a motion to “suppress” the statements that had been extracted him under duress at Camp Rhino. A hearing was scheduled in July 2001, which would have included testimony by John and others about the brutality he had suffered at the hands of US soldiers. On the eve of the hearing, the government prosecutors approached John’s attorneys and negotiated a plea agreement. It was apparent they did not want evidence of John’s torture to be introduced in court.

In the plea agreement John acknowledged that by serving as a soldier in Afghanistan he had violated the anti-Taliban economic sanctions imposed by President Clinton and extended by President Bush. This was, as John’s lawyer pointed out, a “regulatory infraction”. John also agreed to a “weapons charge”, which was used to enhance his prison sentence. In particular, he acknowledged that he had carried a rifle and two grenades while serving as a soldier in the Taliban army. All of the other counts in the indictment were dropped by the government, including the terrorism charges the attorney general had so strongly emphasised and the charge of conspiracy to commit murder in the death of Mike Spann.

At the insistence of defence secretary Rumsfeld, the plea agreement also included a clause in which John relinquished his claims of torture.

The punishment in the plea agreement was by any measure harsh: 20 years of imprisonment, commencing on 1 December 2001, the day John came into the hands of US forces in Afghanistan. The prosecutors told John’s attorneys that the White House insisted on the lengthy sentence, and that they could not negotiate downward.

On 4 October 2002, the judge approved the plea agreement as “just and reasonable” and sentenced John to prison. Before the sentence was pronounced, John was allowed to read a prepared statement, which provided a moment of intense drama in the crowded courtroom. He spoke with strong emotion. He explained why he had gone to Afghanistan to help the Taliban in their fight with the Northern Alliance, saying it arose from his compassion for the suffering of ordinary people who had been subjected to atrocities committed by the Northern Alliance. He explained that when he went to Afghanistan he “saw the war between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance as a continuation of the war between the mujahideen and the Soviets”.

John strongly condemned terrorism. “I went to Afghanistan with the intention of fighting against terrorism and oppression.” He had acted, he said, out of a sense of religious duty and he condemned terrorism as being “completely against Islam”. He said: “I have never supported terrorism in any form and never would.”

After a brief recess, the judge granted a request by John Spann, the father of Mike Spann, to address the court and express his dissatisfaction with the plea agreement. He began by saying that he, his family, and many other people believed that John had played a role in the killing of Mike Spann. Judge Ellis interrupted and said: “Let me be clear about that. The government has no evidence of that.” Spann responded: “I understand.” The judge politely explained that the “suspicions, the inferences you draw from the facts are not enough to warrant a jury conviction”. He said that Mike Spann had died a hero, and that among the things he died for was the principle that “we don’t convict people in the absence of proof beyond a reasonable doubt”.

Osama bin Laden is dead. John Lindh, now 30 years old, remains in prison. He spends most of his time pursuing his study of the Qur’an and Islamic scholarship. He also reads widely in a variety of nonfiction subjects, especially history and politics. He remains a devout Muslim.

As a father, I am grateful that John survived his ordeal, and I am pleased that he maintains his good-natured disposition. I am especially proud of the dignity he displayed throughout his ordeal overseas and in court.

Other than his lawyers, the only visitors John has been permitted during all his years in prison are those of us in his immediate family. We treasure these visits. We are not allowed any sort of physical contact with John, and are kept separated from him by a glass partition. We must speak via telephones, and everything we say is monitored and recorded by a government agent who sits in an adjoining room. Despite these constraints, our conversations are free-flowing and punctuated with humour.

A commentator at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University called this “a petty prosecution” that was “unworthy of a great country”. But it was more than petty, in my view; it was brutally inhumane.

My hope and prayer is that at some point rational, fair-minded officials in the American government will see the wisdom in releasing John from prison, rather than making him serve the entire 20-year sentence. His continued incarceration serves no good purpose. Releasing John from prison would help restore America’s image in the world, and particularly among Muslim people, as a humane country committed to the rule of law.