Feb 20 2011

One of the untold stories of Egypt’s popular revolution is the plight of homeless children caught up in the unrest. As the country adjusted to a new political reality during the protests, Cairo’s estimated 50,000 street children also found that the rules of the game had changed.

The drop-in centres that they rely on for food, clean water and shelter were, like nearly everything else in Egypt, mostly closed. With nothing to eat and nowhere to go, the children were drawn to the festival atmosphere of Tahrir Square, attracted by the prospect of a free meal and the chance of being part of something exciting.

Instead, they found themselves part of something very different. When violence erupted, the homeless children had nowhere to seek refuge and many were caught up in the clashes between rival political factions. Save the Children has confirmed the death of at least one child – a 16-year-old boy called Ismail – and knows of others who were wounded.

But you will not find Ismail’s face staring out of the martyr posters that commemorate the revolution’s fallen. He died as he lived, in the shadows, there but not there, shot dead by an unknown gunman for an unknown reason, another anonymous statistic of Egypt’s lost generation of street children. More than two weeks after his death, his body still lies unclaimed in a hospital morgue.

It does not have to be this way. There is now an opportunity to make small changes that would greatly improve the situation for Egypt’s homeless children. One of the major challenges they face is that they often lack the identity documents that are a passport to basic services such as healthcare and education.

Without them, their already precarious situation is made more serious still. One of the street children who was shot in the protests was turned away from the first hospital her friends carried her to, and was only treated at the second when she looked close to death.

Even healthy street children are made more vulnerable by their lack of identification papers; they face arrest for not carrying IDs and once in custody have no hope of being able to afford any sort of legal representation. While one arm of the state is withholding the documents, the other is punishing the children for not carrying them.

The effect is that these vulnerable children are locked out of Egyptian society and robbed of any hope of lifting themselves out of the desperate poverty that condemns them to a chaotic life on the street. For many, the only education they receive is the literacy classes offered by drop-in centres. It is too little, too late.

If Egyptian street children were issued ID cards, they would be given a sliver of hope, a chance of a brighter future, the opportunity to find legitimate work or enrol in classes that equip them with the basic life skills most Egyptians take for granted.

In the heady days leading up to the revolution, the protestors spoke of a new era of national solidarity, of standing up for their rights, taking control of their destiny. Now the country has the opportunity to make good on those noble ideals, and must make sure no-one – including the poorest – is left behind.

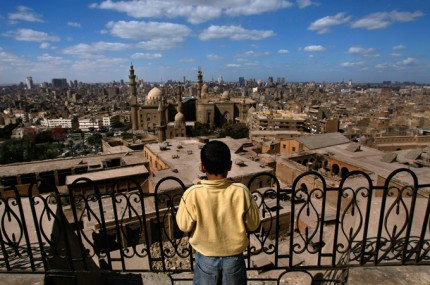

The Egyptian people have sent a clear message that the status quo is no longer acceptable. They are empowered, confident and hungry for change. For the children who eke out an existence on the streets of Cairo, forgotten by the system and ignored by large sections of society, that change cannot come soon enough.