Dec 01 2010

In the heart of the old Chinese capital of Xian stands a minaret like no other I’ve ever seen. It was built to call the faithful to prayer in the city’s Grand Mosque but it has a fishtail roof and is covered in colourful carvings of dragons and flowers.

It is, in other words, a very Chinese minaret in a very Chinese mosque, and one which caters to people who mainly look Chinese as well … though sometimes you get glimpses of features which suggest the owner’s ancestors must have come from elsewhere.

It is a signal of the presence in this city, and in a great swathe right across north-west China, of a Muslim people known today as the Hui.

There are estimated to be 10 million of them – only a drop in the ocean of China’s 1.3 billion – identifiable by the fact that the men wear white caps and the women white headscarves and their communities inevitably sprout minaret towers.

Their presence is a living reminder that the great Silk Road, which once flowed from Xian across northwest China to the outside world, carried not only silk and other trade goods but also the knowledge of inventions such as printing and gunpowder, the religious teachings of Christianity, Buddhism and Islam, and people of many races in search of chances to better themselves.

Some of the Hui’s ancestors were traders who found it more profitable to settle at the start of the Silk Road, in Xian, or in places along the route; others followed when Genghis Khan conquered China and the Yuan dynasty, founded by his grandson, Kublai Khan, sought talented administrators to run the empire; still others were employed by successive emperors as mercenaries.

With them, they brought the Islamic faith but, over the centuries, they gave up their own languages and communicated in Chinese, so today the name Hui effectively refers to Chinese-speaking Muslims.

These immigrants must have been valued subjects because, in 642, the Emperor founded Xian’s Grand Mosque in the heart of his capital for them to worship in.

Down the centuries, it has many times been destroyed by fire and earthquakes, but has always been rebuilt and is still the focal point of an active Islamic community.

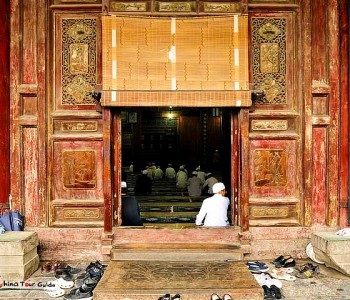

It is a most unusual mosque, the clean lines and curves typical of Islamic architecture being replaced by the complicated shapes of Chinese design, the Islamic prohibition on figures is completely ignored and, instead of inscriptions written in the flowing letters of Arabic, they are mainly in the ideograms of Chinese.

But the basic design is the same as in other mosques, with a minaret from which the muezzin summons the faithful to prayer and a huge prayer hall – which we were not allowed inside – where the worship takes place.

The men often have small beards and usually wear little white caps and the women white head scarves and they mainly seem to live in the area around the Grand Mosque, known as the Muslim Quarter, a place of narrow alleys and quaint old homes.

The members of Xian’s Muslim community also seem to have retained the trading skills of their ancestors because those narrow lanes are lined with stalls selling everything from the dates and silks that would have been carried by the caravans of 1000 years ago to those modern Chinese trade goods, knock-off brand-name clothes and fake watches. I even saw a T-shirt bearing the face of Chairman Mao alongside one showing President Barack Obama in a Mao-style cap with a red star (confirming the suspicions of some Tea Party members).

Driving through the countryside in China’s Shaanxi, Gansu, Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces, you see lots more mosques but of a more traditional Arabic design.

But the Hui in these villages certainly retain the ancestral flair for trading. Their villages are lined with small stalls selling everything from dates and nuts to hats and ornaments.

In one village, a smiling Hui tried to sell me a giant pile of what I think was sheep’s wool.

“Very good for you,” he said. “Your wife will be pleased. Make good clothes.”

I was almost convinced.